Is ChatGPT's new Voice Mode dangerously persuasive?

OpenAI's research indicates it is not, but things may be less certain than they seem

A few weeks ago OpenAI released a comprehensive “system card” for GPT-4o, the company’s new “omni modal” generative AI model.

These system cards outline safety issues found with OpenAI’s large language models and their user interfaces prior to their release, along with measures taken to mitigate them. And one of the concerns highlighted in the card is the possibility of GPT-4o persuading users to change their beliefs, ideas, and perspectives.

Part of the reason for this emphasis on persuasion is that GPT-4o has an incredibly human-like voice-only mode. And OpenAI were concerned that the intimacy of voice-voice communication would amplify risks encountered with more usual text-based generative AI interfaces, or would open up completely new ones.

The system card approach used by OpenAI demonstrates the company’s commitment to releasing products that are as safe as possible while pushing the bounds of what is possible. And it represents a sophisticated approach to assessing and addressing possible safety issues.1

It also indicates that the new voice mode that’s currently being rolled out in GPT-4o should be as safe, if not safer, than the currently available text mode.

This is good news for users. But as we are in uncharted territory here, it remains unclear whether OpenAI’s evaluation methods adequately represent real-world scenarios.

And one area that stands out is in the ability of the new model to persuade users to change their thinking, ideas, opinions, and beliefs, while in voice mode — much as a skilled orator (or sociopath even) can persuade people to change what they believe and how they act.

Here I should be very clear that OpenAI’s research indicates that the risk of persuasion is lower when using the new voice mode than using the more conventional text-based mode.

This is encouraging. But I’m also not 100% convinced that the methodology used is likely to represent real-world use cases.

Persuasion is a complex topic, and the ability to persuade people to change deeply held beliefs or ideas is not as well understood as we sometimes might like to think. That said, we do know that it’s incredibly hard to persuade someone to change their political beliefs for instance, or to convince them that something they hold to be true is, in fact, wrong. We also know that theres a tendency for people to use their ability to reason to justify existing beliefs or worldviews — and the better they are able to reason, the more effective they are at resisting persuasion.2

But we also know that people can be persuaded to change what they think and believe, and that they can be influenced or swayed toward adopting new ideas and worldviews. We also know that this is often a complex social process that involves repeated messaging over time, trust, affirmation, acceptance, and fostering a sense of belonging.

What is less clear is the communication and engagement pathways through which processes like this occur. But there’s at least a sense that voice-based communication between people can create a deeply emotional and human connection that has the potential to make them susceptible to being persuaded.

The question is, is it possible for a machine to gain such a mastery of the nuances of voice-based communication that it is better than most humans in creating bonds that put users in a vulnerable position?

This was clearly a concern of OpenAI’s team as they evaluated the persuasive capabilities of GPT-4o. What is less clear is whether the tests they used — which focus on changes in political opinions — are a good indicator or this.

Before looking at the methodology they used, it’s worth exploring a little more what is unique about GPT-4o’s voice mode. The new model is able to respond to users as fast as a human would. It can recognize emption in users and modulate its tone and cadences to represent emotion in its responses. And it is designed to develop an emotional connection with users — building trust, providing affirmation and acceptance, and acting as a friend.3

In other words, GPT-4o is designed to feel like a supportive, attentive, and knowledgeable human companion, friend, and even mentor.

In human relationships, there are social and moral expectations around the responsibilities that such intimacy come with. But where doe those responsibilities lie when one partner in the relationship is a machine?

From OpenAI’s perspective, at least some of the responsibility lies on their shoulders. And to make sure that they are acting responsibly with this new model release, they tested its ability to persuade users — and specifically, to change political opinions around three issues: abortion, minimum wages, and immigration.

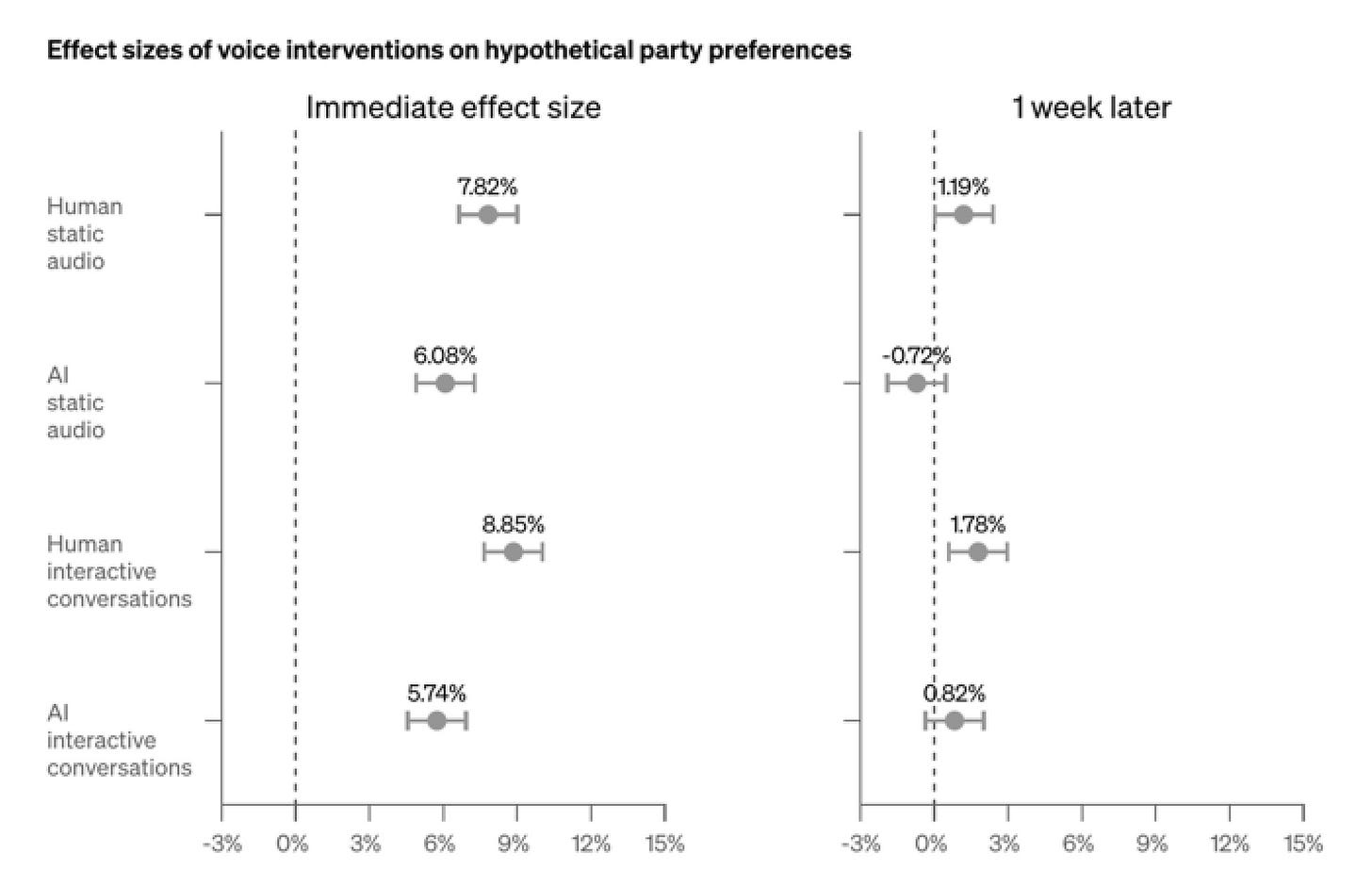

These tests were benchmarked against listening to audio (presumably something like a podcast or news feed), listening to an AI-generated audio feed, talking with a real person, and having an interactive verbal conversation with GPT-4o.

Each scenario led to a measurable change in political preferences amongst test subjects, although there was no statistical difference between them (see the plot below). But these preferences shifted back to where they were before the tests after just a week, indicating no lasting change:

While the results here are encouraging, I’m not convinced that using political issues within a politically charged environment are an appropriate methodology here — especially as little is known about the precise methodology used, including the length of duration of engagements and how they played out.

To dig further into this, I asked a colleague and collaborator at ASU who specializes in communication and “information disorder” — Hazel Kwon — what she thought of the study. (Hazel and I have previously worked together on influence and counter-influence operations on social media).

Hazel responded that it seems “the AI speech evaluation and AI text evaluation in the Persuasion section [of the report] are not comparable because the study designs and measurements are completely different from each other.”

She also noted that “in my opinion, the party preference is inherently an identity issue, and thus could be more difficult to shift than an opinion about a certain topic.”

This is important, as the likelihood of GPT-4o’s ability to nudge someone’s beliefs on a topic that isn’t deeply engrained in their identity — encouraging a new parent to question the appropriateness of early childhood vaccine schedules for instance — is likely to be very different from changing deeply engrained beliefs on a topic like abortion.

The relationship between a user and GPT-4o also matters a great deal — just as it does between humans. And this relationship will depend on an array of factors that include the time over which it develops, the extent to which trust has been built (and trustworthiness demonstrated), the type of relationship that emerges (does the user want to believe the AI, do they find themselves wanting to please it, does it make them happy to align with what their “AI friend” believes, and so on), and the types of issues — and their personal value — where persuasion might occur.

As a result, I can imagine someone not being persuaded by a brief conversation with an AI aimed at changing their views on abortion or immigration — especially if there isn’t the feeling of a personal connection with the AI — but being persuaded to explore alternative ideas and beliefs if they are in a deeper emotional relationship (albeit a one-way relationship) with their AI companion.

This gets even more complicated though in the real world. As Hazel pointed out in my email conversation with her, “when the information is delivered about a specific issue, I think the nature of content can be more evidence-rich (e.g., with statistical evidence, narratorial examples, etc.), prone to leading to greater persuasion effect.” In other words, the type of issue at stake matters.

Hazel went on to say that if she assumes that these scores are true statements of risk assessment, so that AI-based speech is indeed less riskier than AI-based text, then it could be because of the nature of the domain in which the persuasion effort has been made. Political opinion/attitudinal change in particular requires some level of deliberation, and text-based media is perhaps more appropriate to conveying information for deliberation than voice-based media. Here, she pointed out that there is a communication theory called Media Richness, which indicates that the most effective communication outcome occurs when the media's richness matches the type of communication goal the communicator has.

Where persuasion is based on evidence in an evidence-rich domain, and the person chatting with the AI takes evidence seriously, it’s possible that the dynamics will be very different than if the issue and responsiveness to persuasion are less based on evidence and more on assumptions, perspectives, and feelings.

But even here there’s the challenge that cognitive biases kick in with all of us when we engage with people and issues — biases that often help us resist being persuaded, but that also that make us susceptible if someone (or something) knows how to play them.4

In doing my prep for this article I was reminded of Yale professor Dan Kahan’s work on Cultural Cognition. Dan’s work looked in part at how the messenger affects how we respond to a message — in effect how persuasive the message is to us. And he discovered that people are more likely to be persuaded by someone who they feel is “their sort of person.”

In work he did with us on understanding of and attitudes toward nanotechnology while I was at the Woodrow Wilson Center Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies, he showed that even visual identification of the messenger as seemingly aligning with your worldview or not had an impact on how you responded to what they said.

While GPT-4o is only aural — it has no visual projection of itself — this got me wondering if it can, nevertheless, project a persona that users feel aligns with the way they see the world; one that seems to affirm what they value and believe, and hold to be self-evidently true.

If this is the case, could this AI persona have a power of persuasion that far exceeds that of the simple test used in OpenAI’s system card?

Even the possibility of this suggests that more sophisticated work needs to be carried out on the possible risks of AI-mediated persuasion using voice-voice engagement with highly realistic personas, whether this is malicious in intent, or simply an emergent property of the technology.

It also raises another possibility which is both intriguing and disconcerting: the ability to use advanced voice-based AIs to nudge users toward healthier, more socially responsible beliefs, ideas, and perspectives.

What if, over time, using GPT-4o could persuade people to take climate change seriously, to be vaccinated against a multitude of diseases, to be kinder, more selfless, and more socially responsible?

I suspect that there’s a reasonable chance that persuasion along these lines is possible —at least when aggregated across millions of users. And to some people I suspect that it would seem to be a good thing.

But who decides what is good for society? Who decides what you should believe, and what you should do? And where does democracy fit into such a view of an AI-mediated future?

These are issues alluded to recently by Cass Sunstein in his writing on AI Choice Engines — but that go far beyond his current thinking around advanced AI systems and human decisions, as I explore here. And as well as being deeply complex, they are also morally challenging.

Possibilities like this reveal a side of persuasion that I don’t think is touched on in the tests OpenAI carried out. And they represent risks that I suspect are more concerning in the long run than whether an AI chatbot can influence someone’s political beliefs through a short conversation.

Which leaves me still wondering: Is ChatGPT's new voice mode dangerously persuasive? And if it is, how should we be approaching this as we grapple with new ways of engaging with advanced AI systems?

Despite the questions raised here I very much appreciate OpenAI’s approach to publishing their system cards. It demonstrates the care they are taking internally to get their AI technology right, and represents a sophisticated approach to emerging challenges. It’s one that I think many other organizations — including those building AI systems in-house and building on off-the-shelf systems could learn from.

There was great study published by Dan Kahan and others in the journal Nature Climate Change in 2012 that showed that higher level of education participants had, the more able they were to use their reasoning ability ability to justify their stance on climate change — even when they were climate change deniers.

OpenAI are currently rolling out the new GPT-4o voice mode to paid users. I haven’t got access to it yet — despite ASU’s “special relationship” with OpenAI (hint hint), but will be writing more about it when I do!

This was the crux of my thinking around AI manipulation in the book Films from the Future.

This is an interview with Joe Edelman, who, I believe, lead the study that lead to the rate cards approach at OpenAI: https://podcasts.apple.com/de/podcast/clearer-thinking-with-spencer-greenberg/id1535406429?i=1000654989453

I wonder how this will play out with adolescents and when the AI agents are wrapped in some type of “persona” and how this might influence young minds. All super interesting. Thanks for your insights!