AI Choice Engines, Paternalism, and Behavioral Manipulation

Digging into a new commentary by Cass Sunstein focused on using AI to help individuals make informed choices.

Cass Sunstein has a new commentary in the journal Nature: Humanities & Social Science Communications on the potential benefits and risks of AI-based “Choice Engines.”

Intrigued by the ideas and arguments he puts forward, I wanted to dig a little deeper into where these might lead.

The concept of Choice Engines dates back to a 2013 paper in the Harvard Business review by Richard Thayler and Will Tucker.

Thayler and Tucker argue that consumers are “constantly confronted with information that is highly important but extremely hard to navigate or understand” when making decisions such as what to buy to what to eat, and that the inability of people to make decisions that are ultimately good for them “indicates the fundamental difficulty of explaining anything complex in simple terms.”

Their solution: technologies that assimilate and interpret vast amounts of data in ways that allow individuals to make decisions tailored to their needs.

Such “Choice Engines” have been experimented with for some years now as a way of helping or “nudging” people to make smart decisions. But advances in AI have brought the vision of machines that can help each of us make the best decisions for our future wellbeing much closer — and this is what Sunstein grapples with in his new commentary.

Sunstein’s arguments can be summed up quite succinctly:

Individuals are often confounded by deficits in information and behavioral biases when making decisions — especially decisions with long term consequences — that lead to personal welfare being poorly optimized.

Attempts to nudge people toward better decisions using mechanisms such as labels or other forms of information tend to fail because they’re a blanket solution to a heterogeneity of individual contexts and behaviors.

Emerging AI capabilities could be used to develop powerful “Choice Engines” that combat lack of information and behavioral biases to ensure decisions that optimize welfare at the individual level.

Such a capability raises substantial social and ethical questions, from the degree to which paternalistic Choice Engines take agency away from individuals, to their possible use in cynically manipulating people.

At the heart of these arguments is a suite of complex questions around the “could” of AI-based Choice Engines versus the “should” of technologies that, while designed to increase individual welfare, risk threatening value in unexpected ways.

Sunstein touches on some of these challenges in his commentary, including the levels of paternalism that may or may not be acceptable, and the use of such engines to manipulate people’s behaviors in ways that are designed to benefit others. But it stops short on speculating much further than this.

Reading commentary, I was interested in pushing the ideas in it a little further — especially with respect to manipulation (something I’ve written about before).

Some of my concerns around manipulation in particular were touched on in the paper “The Ethics of Advanced AI Assistants” published by researchers at Google earlier this year.

Here, the paper’s authors state that “Advanced AI assistants are likely to have the ability to influence user beliefs and behaviour (sic) through rational persuasion, alongside potentially malign techniques such as manipulation, coercion, deception and exploitation” (Chapter 9).

This manipulation could be unintended — such as when the feedback loop between a user and an AI platform like Claude or ChatGPT leads to behavioral nudges that aren’t intentional, but may still not be in someone’s best interests.

Or it may be highly intentional — such as the use of AI images, messaging, and engagement, that taps into someone’s cognitive biases in ways that lead to their behavior being steered in directions that benefit others more than themselves.

These aren’t the types of AI Choice Engine uses that are directly addressed by Sunstein. But here’s the rub — the capabilities that make socially beneficial AI Choice Engines viable are the same as those that make AI-driven persuasion and manipulation possible.

And this makes navigating the emerging capabilities of AI to influence personal decisions all the more challenging.

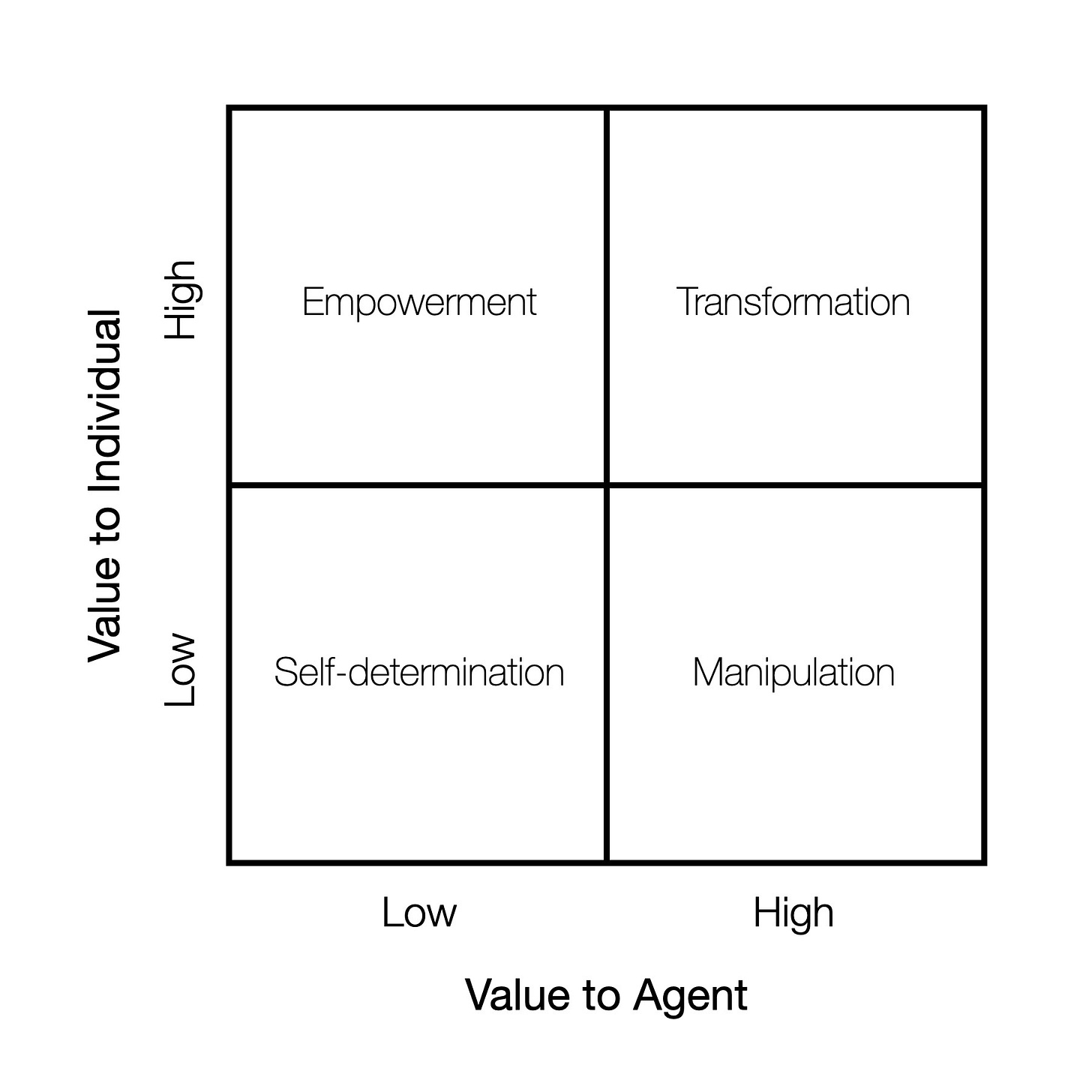

To explore this further, I was interested in exploring how value to the individual potentially aligns with or against value to an “agent” that’s developing and deploying an AI choice agent — whether this is a government agency, corporation, not-for-profit, or some other form of organization.

The result was a simple quadrant diagram that, nevertheless, offers some insights:

Where the value of an AI Choice Engine to both the agent and the individual is low, there’s unlikely to be an incentive to create highly persuasive engines, leaving individuals with a larger number of choices and more latitude to make decisions untainted by AI (the Self-Determination quadrant).

On the other hand, where the value of an AI Choice Engine is high to the individual but low to the agent, most of the incentive will lie in maximizing individual value, in particular welfare/wellbeing. This is the Empowerment quadrant in the quickly sketched out diagram.

This quadrant might be envisioned as representing the ideal scenario for AI Choice Engines — especially those used by governments … apart from the issue that the notion of an agent that minimizes value to itself in favor of others is highly naive, even in the case of governments.

In contrast, where value is high to the agent but low to the individual, AI Choice Engines are likely to veer into becoming engines of manipulation (the bottom right Manipulation quadrant).

And finally, there’s the seeming win-win situation where both individual and agent benefit from AI Choice Engines — the Transformation quadrant. This would seem to be the ideal outcome, although there’s always the danger of brittle solutions where there’s precarious tension between value creation for individuals and that for agents.

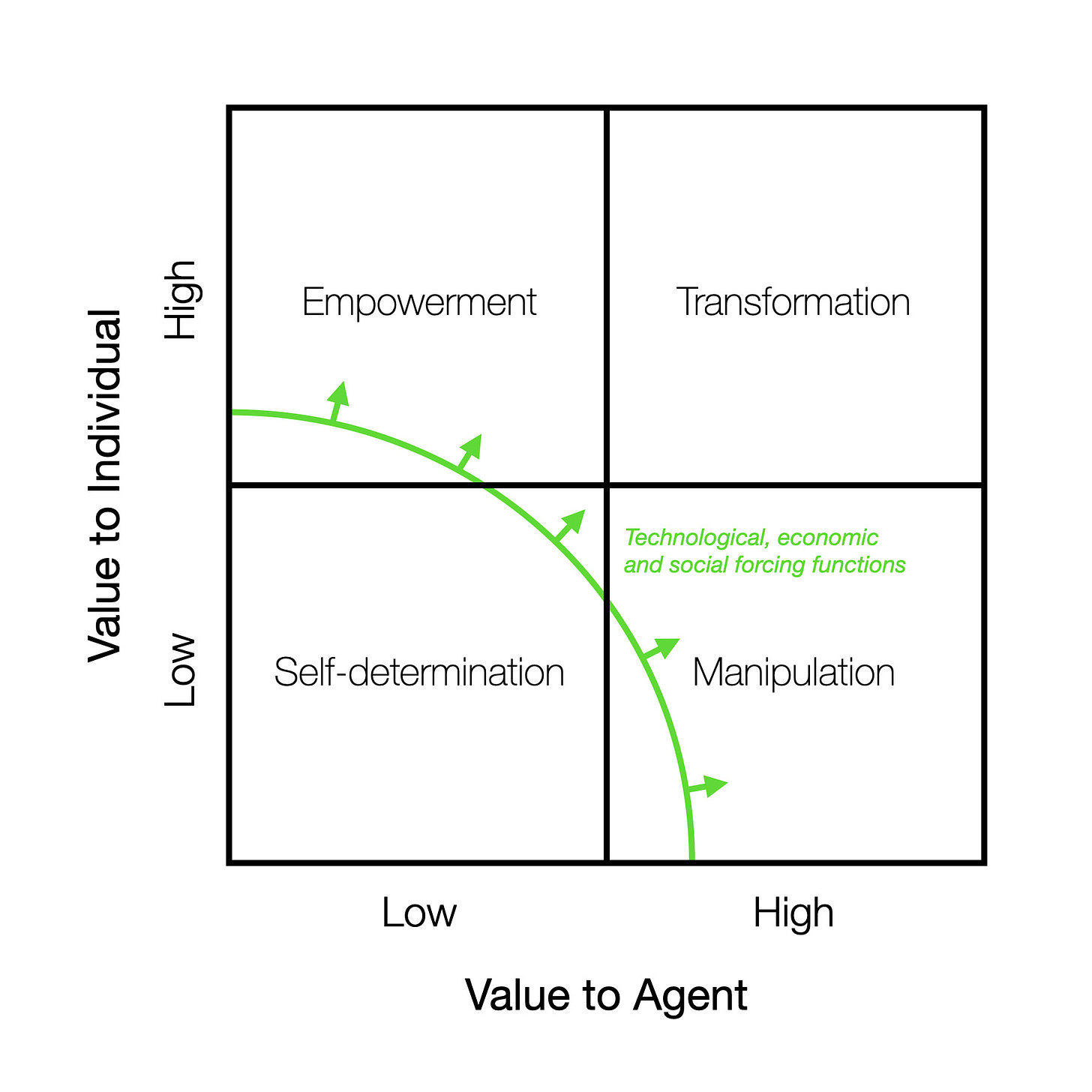

As I’ve hinted above, within this quadrant diagram there are forcing functions and factors that make some scenarios more likely than others, unless provisions are put in place to constrain the development and use of AI Choice Engines along socially responsible lines.

First off, it’s reasonable to assume that there are a number of economic and societal factors at play that are only going to lead to increasingly powerful AI Choice Engines emerging over time:

Here it’s highly likely that technological innovation and advances are inevitable given our human nature, together with a suite of societal and economic dynamics that are near-impossible to resist. This means that movement away from the bottom left quadrant is extremely likely.

The question then becomes not one of whether AI Choice Engines will impact our lives, but how and when their impact will become manifest — and which of the three remaining quadrants we’ll end up in.

And this is where the dynamics between individual versus agent value creation are likely to come into play:

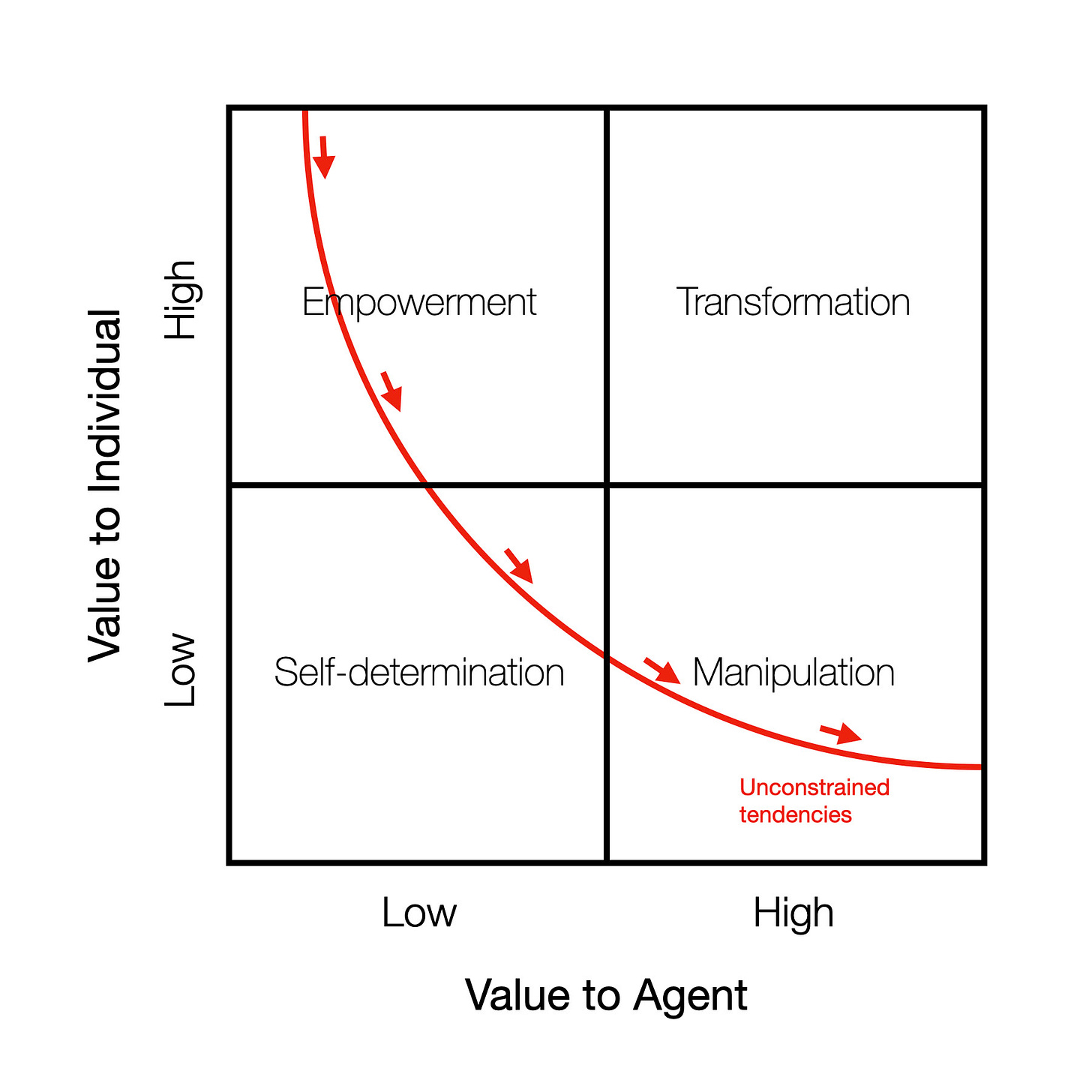

The diagram above is admittedly rather simplistic. But it’s reasonable to assume that value to agents (including governments, for-profits, not for profits etc.) is likely to dominate the future of AI Choice Engines in an unconstrained environment, simply because this is where the power and impetus lies.

The result — if measures that resist this natural flow aren’t put in place — leaves individuals as engines of value creation rather than the primary recipients of created value. And indeed, this is a tendency that’s already been seen extensively with the monetization of data.

In other words, there’s likely to be an economic gradient that pulls the impact of future AI Choice Engines toward being used for manipulation rather than empowerment.

This may not be intentional or even malicious. But without guardrails in place, including well-crafted policies and other barriers to restrict unconstrained tendencies, AI Choice Engines are likely to be used to maximize value creation for those that have the ability to do so.

For instance, imagine a hypothetical federal agency concludes that eating fewer calories and a predominantly plant-based diet will enhance individual and population welfare in the long term, while substantially decreasing healthcare costs and increasing GDP. In this scenario AI Choice Engines could conceivably be developed and deployed that use individually tailored nudging to change eating habits across the nation.

This may seem like a reasonable idea, until the value to the agent — the federal agency and it’s leaders and stakeholders in this case — is considered. This is likely to include increasing power and influence, supporting government policies (which are likely rooted in ideology and unlikely to be universally shared), and benefitting key stakeholders — all good for the agency, but not necessarily so good for all individuals being influenced.

This is also where paternalism raises its head, and tensions around who decides what is good for individuals, and where the true value creation associated with paternalistic control lies.

In other words, the irresistible pull toward power and influence is likely to move even governments toward the manipulation quadrant without appropriate checks and balances in place.

Things are, of course, much more transparent with for-profits, where their fiduciary responsibility to maximize value in terms of profit quite clearly encourages them to slide down the economic gradient toward the lower right quadrant.

For other organizations value creation can be more complex to parse out — but there is always an organizational value proposition that informs the decisions it makes and how power and influence are wielded — and despite any claims to the contrary, this is rarely purely in the interest of all individuals impacted by how power and influence are used.

Given this, how should the development and use of AI Choice Engines be approached in socially responsible ways?

Here, Sunstein kickstarts an important conversation in his commentary. This includes outlining the potential dangers of AI Choice Engines that, “[r]ather than correcting an absence of information or behavioral biases … exploit them”; of Choice Engines that “replicate some of the problems of ‘mass’ interventions”; and AI Choice Engines that suffer from their own behavioral biases — and possibly some that are unique to AI.

And he concludes that “Choice Engines powered by AI have considerable potential to improve consumer welfare and also to reduce externalities, but without regulation, we have reason to question whether they will always or generally do that …. Those who design Choice Engines may or may not count as fiduciaries, but at a minimum, it makes sense to scrutinize all forms of choice architecture for deception and manipulation, broadly understood.”

Considering that these selfsame choice architectures are more likely to favor value creation for those that develop and deploy them than they are for those that use them, there’s a growing need for new thinking on how to resist the economic gradient toward manipulation, and how to push AI Choice Engines up toward the empowerment quadrant or the transformation quadrant.

And this a need that’s increasing in urgency as we get closer to advanced AI assistants that also act as advanced AI Choice Engines — including engines that may, one day, serve the goals of machines as well as humans.

Update: While writing this I was trying to find a quote from OpenAI on AI manipulation and persuasion, but didn’t pin it down in time. However, reading the latest article from Mark Daley reminded me of this interview with OpenAI’s Mira Murati:

In it she says “I do think there are major risks around persuasion … where, you know, you could persuade people very strongly to do specific things. You could control people to do specific things. And I think that’s incredibly scary to control society to go in a specific direction. With the current systems, they’re very capable of persuasion and influencing your way of thinking and your beliefs …”

Sounds like the bottom right quadrant!