Making Sense of Superintelligence

An excerpt from Chapter Eight of “Films from the Future: The Technology and Morality of Sci-Fi Movies”

From Chapter Eight of Films from the Future: The Technology and Morality of Sci-Fi Movies

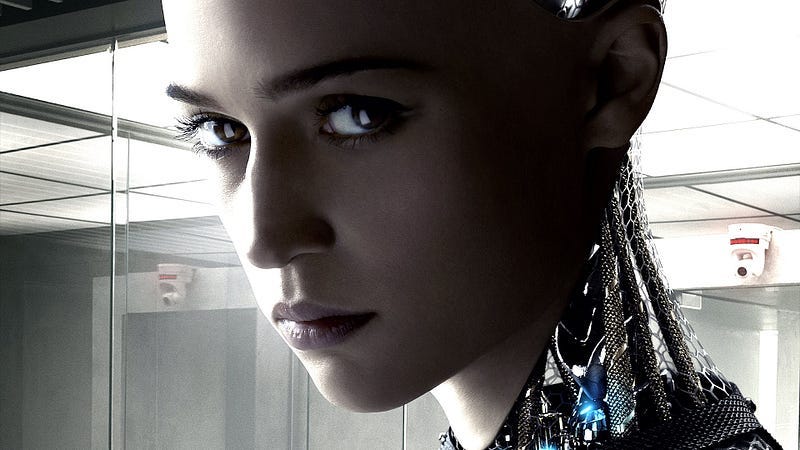

Each week between now and November 15th (publication day!) I’ll be posting excerpts from Films from the Future: The Technology and Morality of Sci-Fi Movies This week, it’s chapter eight, and the movie Ex Machina.

This excerpt doesn’t mention the movie directly, but rather explores the idea of “superintelligence”. In the book, this is part of a broader discussion around plausible technology trends and the nature of intelligence.

In January 2017, a group of experts from around the world got together to hash out guidelines for beneficial artificial intelligence research and development. The meeting was held at the Asilomar Conference Center in California, the same venue where, in 1975, a group of scientists famously established safety guidelines for recombinant DNA research. This time, though, the focus was on ensuring that research on increasingly powerful AI systems led to technologies that benefited society without creating undue risks. And one of those potential risks was a scenario espoused by University of Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom: the emergence of “superintelligence.”

Bostrom is Director of the University of Oxford Future of Humanity Institute, and is someone who’s spent many years wrestling with existential risks, including the potential risks of AI. In 2014, he crystallized his thinking on artificial intelligence in the book Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers and Strategies, and in doing so, he changed the course of public debate around AI. I first met Nick in 2008, while visiting the James Martin School at the University of Oxford. At the time, we both had an interest in the potential impacts of nanotechnology, although Nick’s was more focused on the concept of self-replicating nanobots than the nanoscale materials of my world. At the time, AI wasn’t even on my radar. To me, artificial intelligence conjured up images of AI pioneer Marvin Minsky, and what was at the time less than inspiring work on neural networks. But Bostrom was prescient enough to see beyond the threadbare hype of the past and toward a new wave of AI breakthroughs. And this led to some serious philosophical thinking around what might happen if we let artificial intelligence, and in particular artificial general intelligence, get away from us.

At the heart of Bostrom’s book is the idea that, if we can create a computer that is smarter than us, it should, in principle, be possible for it to create an even smarter version of itself. And this next iteration should in turn be able to build a computer that is smarter still, and so on, with each generation of intelligent machine being designed and built faster than the previous until, in a frenzy of exponential acceleration, a machine emerges that’s so mind- bogglingly intelligent it realizes people aren’t worth the trouble, and does away with us.

Of course, I’m simplifying things and being a little playful with Bostrom’s ideas. But the central concept is that if we’re not careful, we could start a chain reaction of AI’s building more powerful AIs, until humans become superfluous at best, and an impediment to further AI development at worst.

The existential risks that Bostrom describes in Superintelligence grabbed the attention of some equally smart scientists. Enough people took his ideas sufficiently seriously that, in January 2015, some of the world’s top experts in AI and technology innovation signed an open letter promoting the development of beneficial AI, while avoiding “potential pitfalls.” Elon Musk, Steve Wozniak, Stephen Hawking, and around 8,000 others signed the letter, signaling a desire to work toward ensuring that AI benefits humanity, rather than causing more problems than it’s worth. The list of luminaries who signed this open letter is sobering. These are not people prone to flights of fantasy, but in many cases, are respected scientists and successful business leaders. This in itself suggests that enough people were worried at the time by what they could see emerging that they wanted to shore the community up against the potential missteps of permissionless innovation.

The 2017 Asilomar meeting was a direct follow-up to this letter, and one that I had the privilege of participating in. The meeting was heavily focused on the challenges and opportunities to developing beneficial forms of AI. Many of the participants were actively grappling with near- to mid-term challenges presented by artificial- intelligence-based systems, such as loss of transparency in decision- making, machines straying into dangerous territory as they seek to achieve set goals, machines that can learn and adapt while being inscrutable to human understanding, and the ubiquitous “trolley problem” that concerns how an intelligent machine decides who to kill, if it has to make a choice. But there was also a hard core of attendees who believed that the emergence of superintelligence was one of the most important and potentially catastrophic challenges associated with AI.

This concern would often come out in conversations around meals. I’d be sitting next to some engaging person, having what seemed like a normal conversation, when they’d ask “So, do you believe in superintelligence?” As something of an agnostic, I’d either prevaricate, or express some doubts as to the plausibility of the idea. In most cases, they’d then proceed to challenge any doubts that I might express, and try to convert me to becoming a superintelligence believer. I sometimes had to remind myself that I was at a scientific meeting, not a religious convention.

Part of my problem with these conversations was that, despite respecting Bostrom’s brilliance as a philosopher, I don’t fully buy into his notion of superintelligence, and I suspect that many of my overzealous dining companions could spot this a mile off. I certainly agree that the trends in AI-based technologies suggest we are approaching a tipping point in areas like machine learning and natural language processing. And the convergence we’re seeing between AI-based algorithms, novel processing architectures, and advances in neurotechnology are likely to lead to some stunning advances over the next few years. But I struggle with what seems to me to be a very human idea that narrowly-defined intelligence and a particular type of power will lead to world domination.

Here, I freely admit that I may be wrong. And to be sure, we’re seeing far more sophisticated ideas begin to emerge around what the future of AI might look like — physicist Max Tegmark, for one, outlines a compelling vision in his book Life 3.0. The problem is, though, that we’re all looking into a crystal ball as we gaze into the future of AI, and trying to make sense of shadows and portents that, to be honest, none of us really understand. When it comes to some of the more extreme imaginings of superintelligence, two things in particular worry me. One is the challenge we face in differentiating between what is imaginable and what is plausible when we think about the future. The other, looking back to chapter five and the movie Limitless, is how we define and understand intelligence in the first place.

With a creative imagination, it is certainly possible to envision a future where AI takes over the world and crushes humanity. This is the Skynet scenario of the Terminator movies, or the constraining virtual reality of The Matrix. But our technological capabilities remain light-years away from being able to create such futures — even if we do create machines that can design future generations of smarter machines. And it’s not just our inability to write clever-enough algorithms that’s holding us back. For human- like intelligence to emerge from machines, we’d first have to come up with radically different computing substrates and architectures. Our quaint, two-dimensional digital circuits are about as useful to superintelligence as the brain cells of a flatworm are to solving the unified theory of everything; it’s a good start, but there’s a long way to go.

Here, what is plausible, rather than simply imaginable, is vitally important for grounding conversations around what AI will and won’t be able to do in the near future. Bostrom’s ideas of superintelligence are intellectually fascinating, but they’re currently scientifically implausible. On the other hand, Max Tegmark and others are beginning to develop ideas that have more of a ring of plausibility to them, while still painting a picture of a radically different future to the world we live in now (and in Tegmark’s case, one where there is a clear pathway to strong AGI leading to a vastly better future). But in all of these cases, future AI scenarios depend on an understanding of intelligence that may end up being deceptive…

Read more in Films from the Future: The Technology and Morality of Sci-Fi Movies, available at Amazon.com, Barnes and Nobel, Indie Bound, and elsewhere.

Originally published at 2020science.org on October 4, 2018.