Reimagining learning and education in an age of AI

Reflections and provocations from a keynote given at the 2025 Yidan Prize Conference

This past week I was honored to give a keynote on AI and the future of learning and education at the 2025 Yidan Price Conference. As keynotes often are, it was intended to be a little provocative and to get people thinking. And hopefully I didn’t disappoint.

It’s always hard to gauge whether such presentations are worth writing about, or whether they should be seen as a one-off snapshot of the speaker’s thinking at a particular time and place. But on the off chance that there is something here that someone might find useful and interesting, I thought I’d capture the essence of the talk below.

What does the future look like?

The Yidan Prize was established in 2016 as a global foundation committed to creating a better world through education. Each year, two prizes are awarded to individuals who are addressing critical issues in education in innovative and transformative ways — one focused on education research, and one on education development.

In 2023 Arizona State University professor Michelene (Micki) Chi was awarded the prize for Education Research, and to celebrate this ASU’s Mary Lou Fulton College of Teaching and Learning Innovation co-hosted this year’s Yidan Prize Conference on the theme of meeting the future of teaching and learning. And that’s where my keynote came in.

Somewhere in our pre-conference discussions, the title “What does the future look like?” emerged for the keynote, and stuck — a rather daunting brief as, week by week, I’m less sure what the future holds given the current rate of social and technological change. But it did provide me with the opportunity to talk about how emerging and transformative technologies — AI in particular — are challenging many of the assumptions that underlie how we currently approach learning and education; and how we can start to reimagine them.

Reimagining education in a time of unprecedented social and technological acceleration

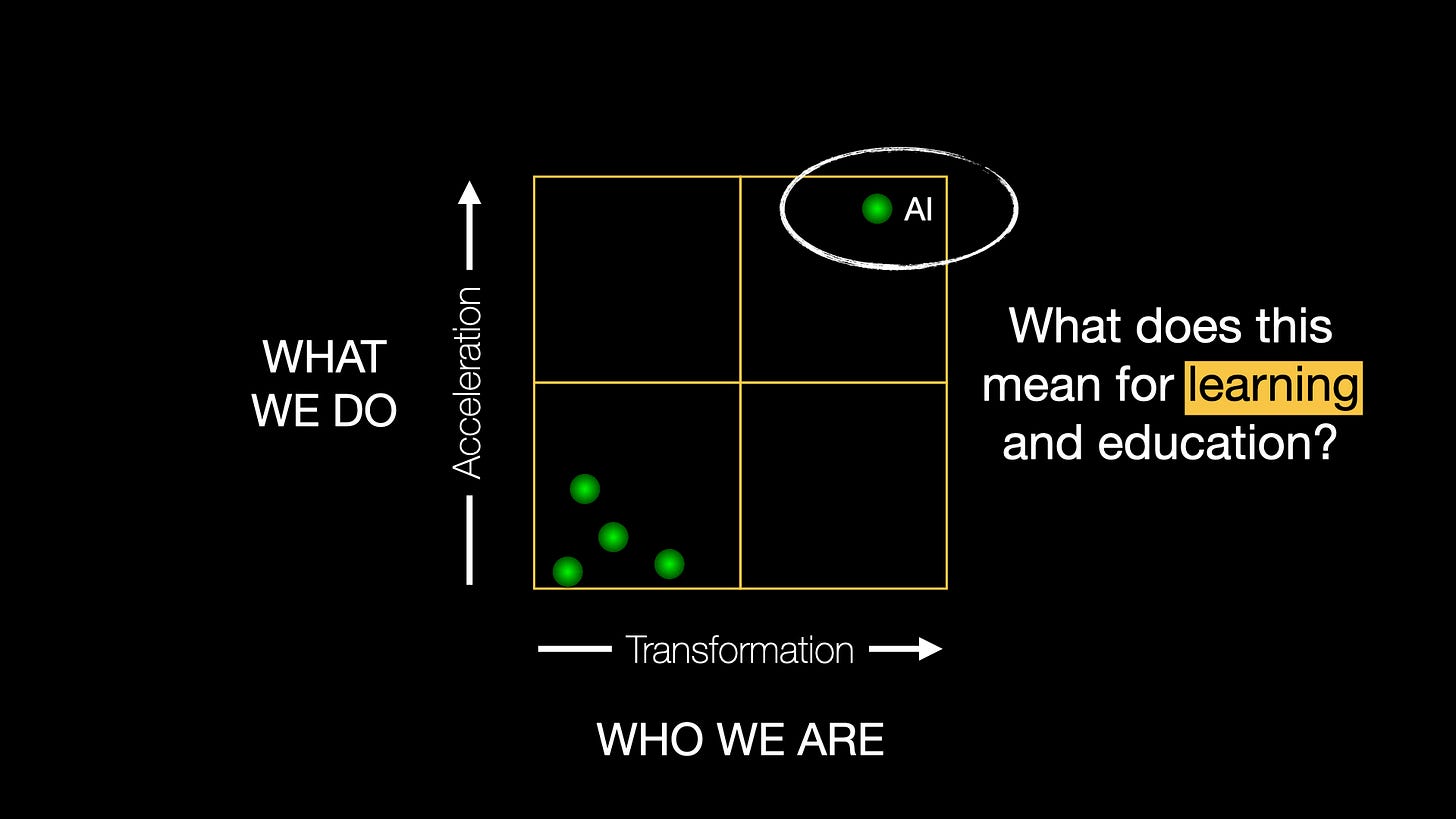

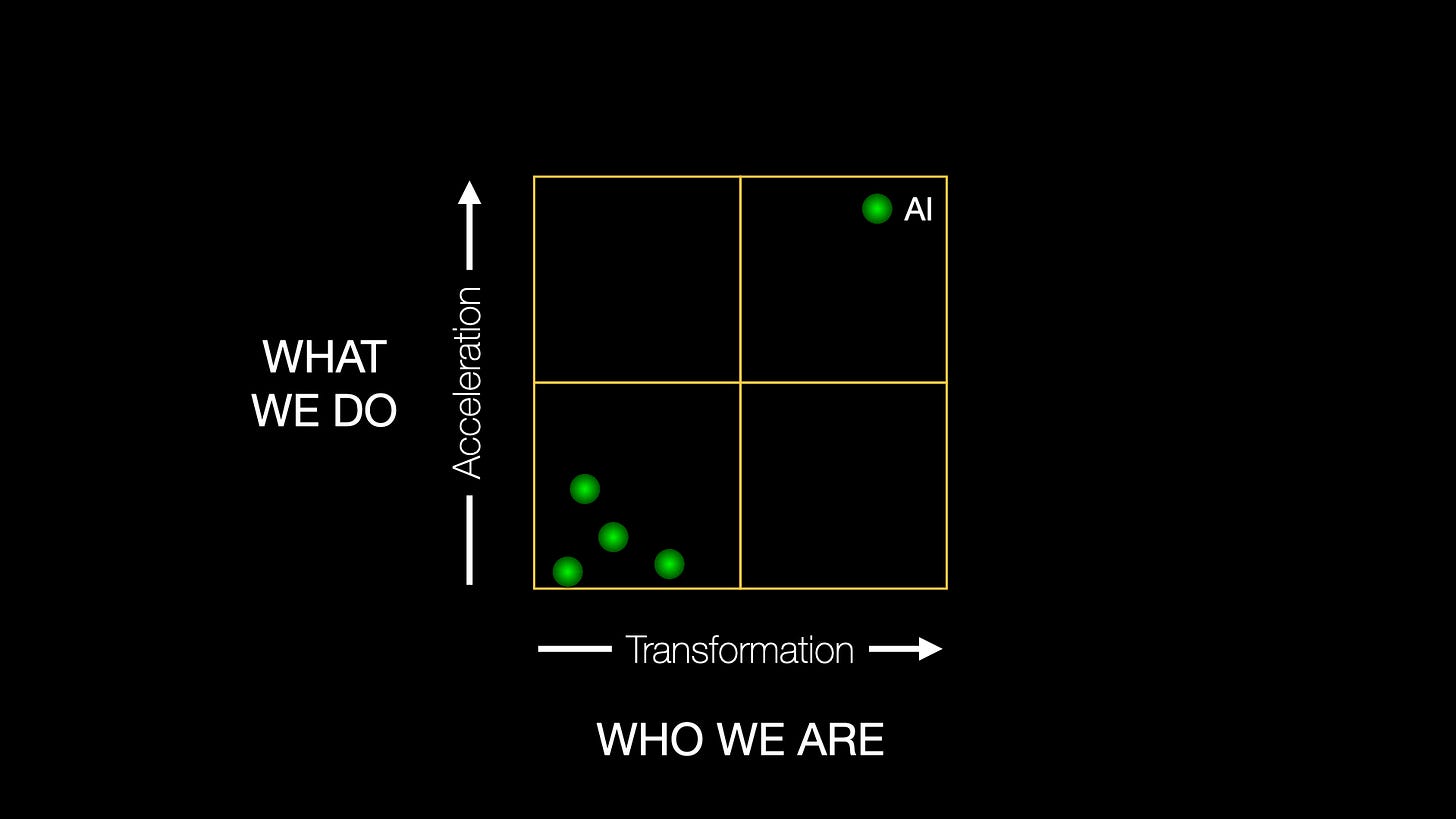

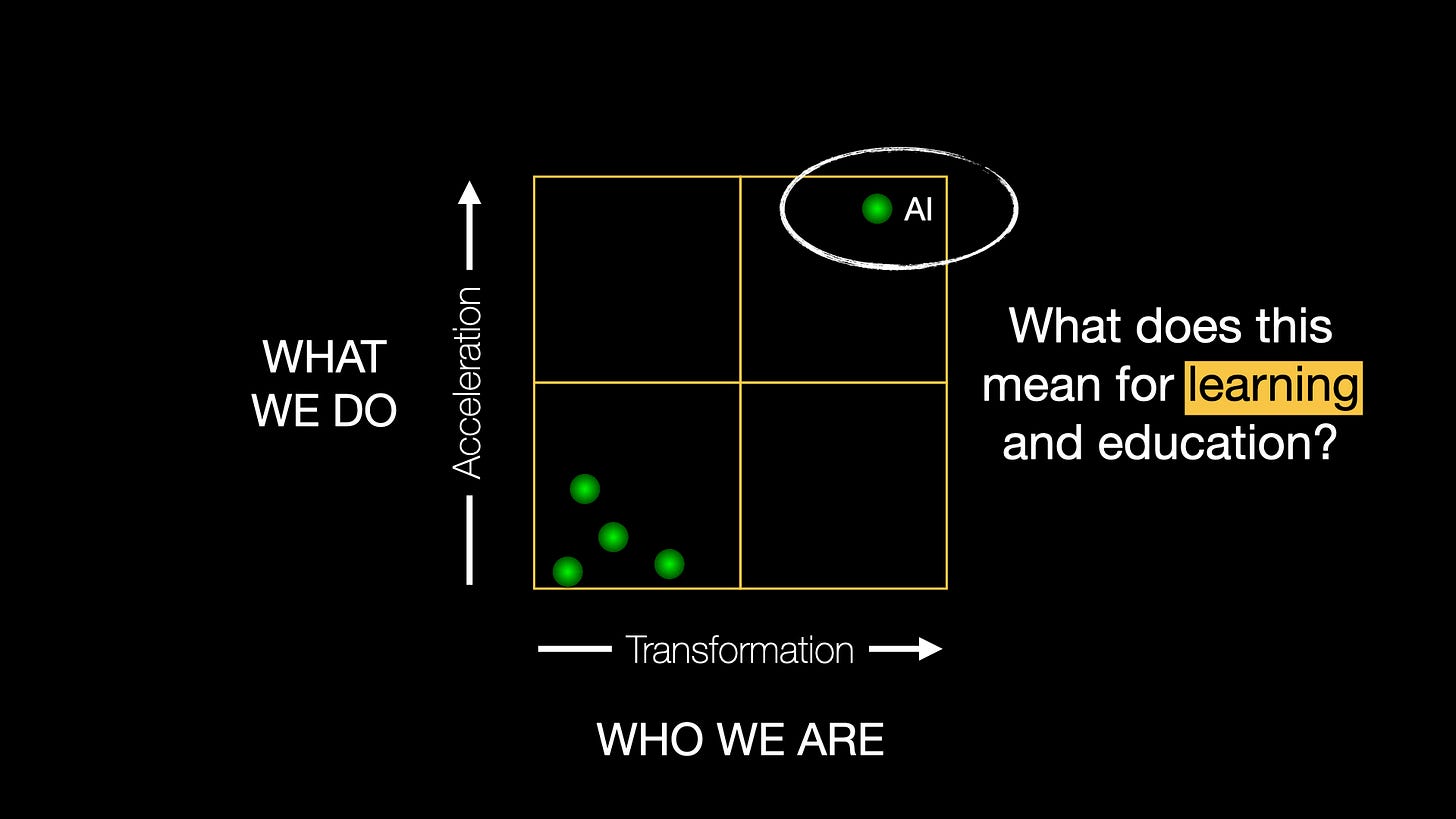

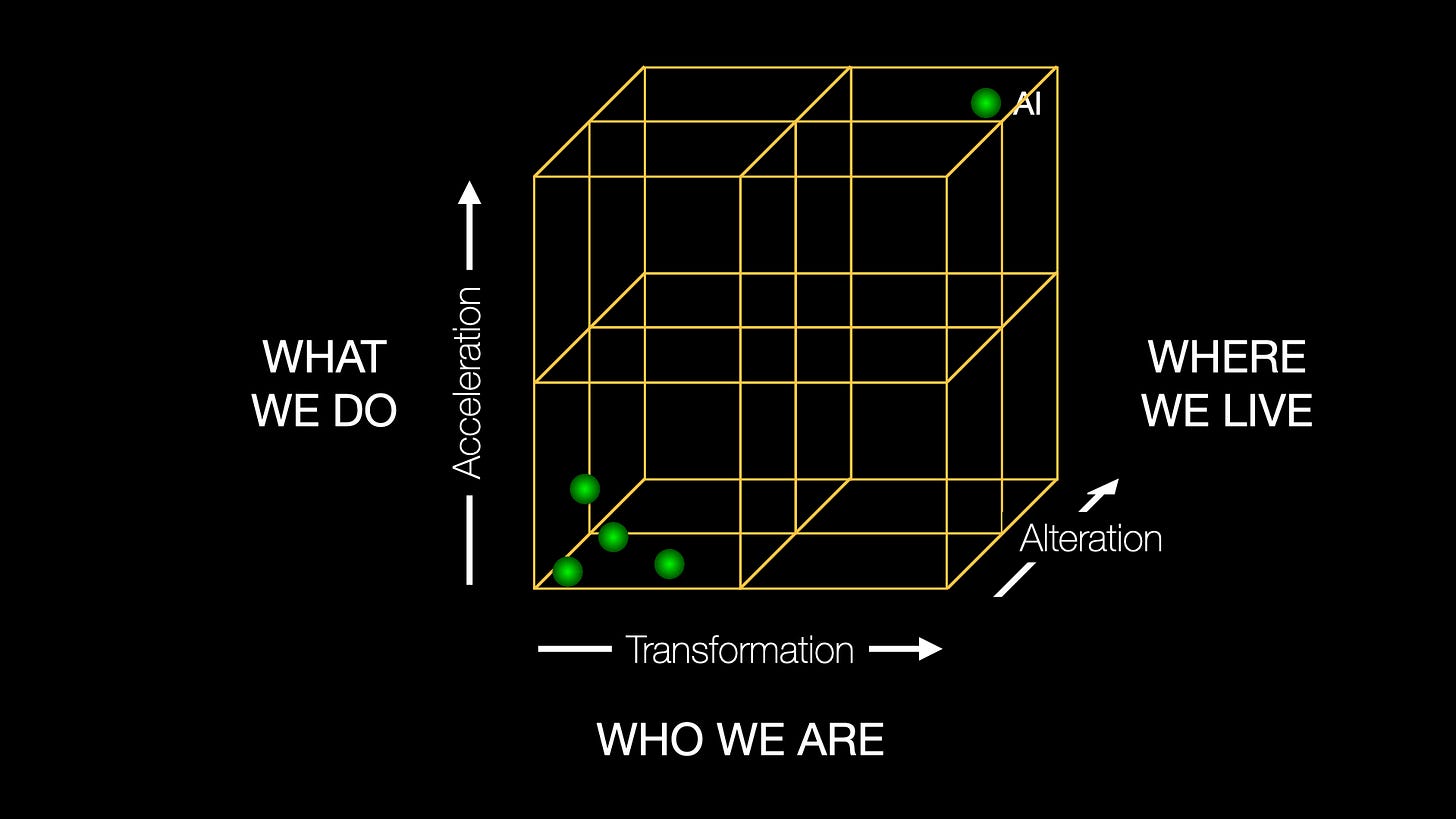

My framing for the keynote was a conceptual model that I find myself using increasingly frequently: how transformative technologies are changing what we do, and who we are.

Of course, technology innovation has been impacting what we do and who we are for pretty much all of human history. But it’s a useful way of beginning to think about how technologies like AI have the potential to push us far further along these two axes than previous technology transitions.

To capture the possibilities here I kicked off with quotes from two prominent thinkers and commentators on AI: Anthropic’s CEO Dario Amodei, and Western University’s Chef AI Officer Mark Daley:

“my basic prediction is that AI-enabled biology and medicine will allow us to compress the progress that human biologists would have achieved over the next 50-100 years into 5-10 years. I’ll refer to this as the “compressed 21st century”: the idea that after powerful AI is developed, we will in a few years make all the progress in biology and medicine that we would have made in the whole 21st century.”

Dario Amodei, October 2024

“We’ve long used technology to amplify our abilities: to dig deeper, run faster, store more data. But now we’re building machines that can think, and that cuts to the heart of who we are. For better or worse, that distinction sets AI on a different plane than plumbing or electricity. And it’s in that difference that our greatest societal, existential, and imaginative challenges lie.”

Mark Daley, March 2025

Both of these perspectives push the limits of our imagination, but are nevertheless critical to thinking about how coming waves of AI potentially challenge deeply held beliefs about our relationship with technology and the future: Dario’s with respect to how transformative technologies are transforming what we do, and Mark’s on how they are transforming who we are.

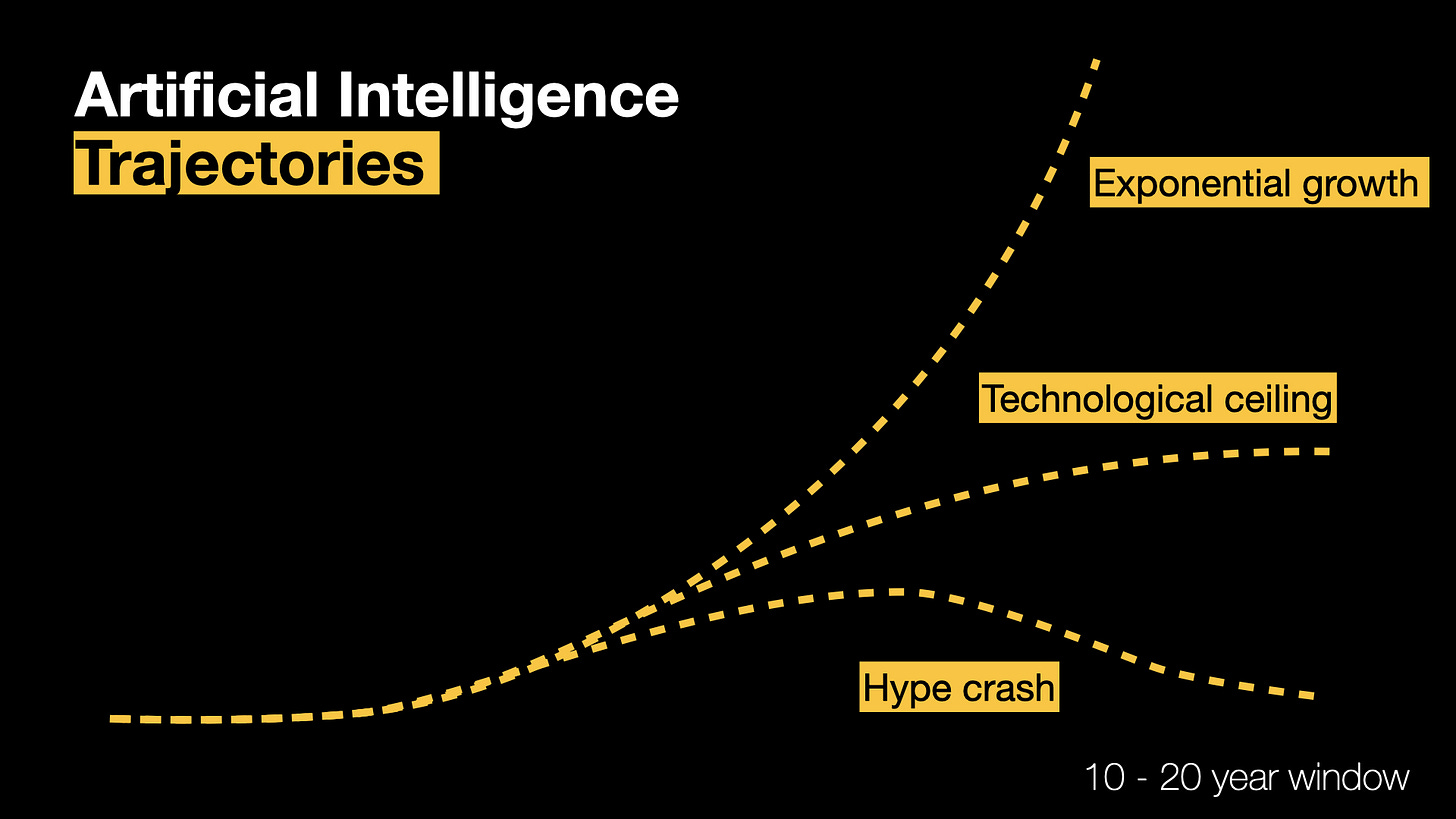

Of course, both are dependent on the trajectory that AI foundation and frontier models take over the next few years, and I was up-front in the talk in noting that there’s a lot of uncertainty here.

There is a possibility that AI capabilities are currently over hyped and we’re heading for yet another AI “winter.” It’s even more likely in my perspective that we’ll see AI follow a classic innovation “S” curve and hit a ceiling at some point — although it’s very unclear indeed when that ceiling might occur, and what might come next. Or we may continue to see exponential growth in capabilities over the next 10 - 20 years — a more speculative projection, but one that has some credence.

No matter which trajectory ends up being closer to the truth, even if there’s a chance that we’re going to see substantial growth in AI capabilities over the next couple of decades, we need to take these this possibility seriously.

If AI poised to be as fundamentally transformative as Dario, Mark and others (including myself) believe it could be, we need to face the likelihood that the ways it accelerates what we are capable of (including acting as an accelerant in virtually every domain of technology innovation), and transforms who we are — and who we understand ourselves to be — put it in a fundamentally different category to every previous technology that we’ve developed as a species.1

This possibility — even if it’s small — demands new ways of thinking about the potentially profound future impacts of what we are creating. And this extends to learning and education.

Of course, as I mentioned earlier, my keynote was intended to get people thinking, and so there’s a lot of hand waving here. But the framing above was intended to set the scene for three challenges/provocations.

Before I got to those in the talk though, there was one more piece of the framing puzzle that I needed to add: the question of why we think learning and education are important in the first place.

Did I mention that I was aiming to be provocative?

Why are learning and education important?

Posing the question of why learning and education are important to a room full of educators was, admittedly, a little risky. Surely everyone knows why they matter! The reality though is that it’s nearly impossible to think about the future of learning and education in an age of AI if we don’t go back to basics and remind ourselves why they’re important, rather than simply assuming they are (or worse, rationalizing their importance simply because we’ve always been told they matter).

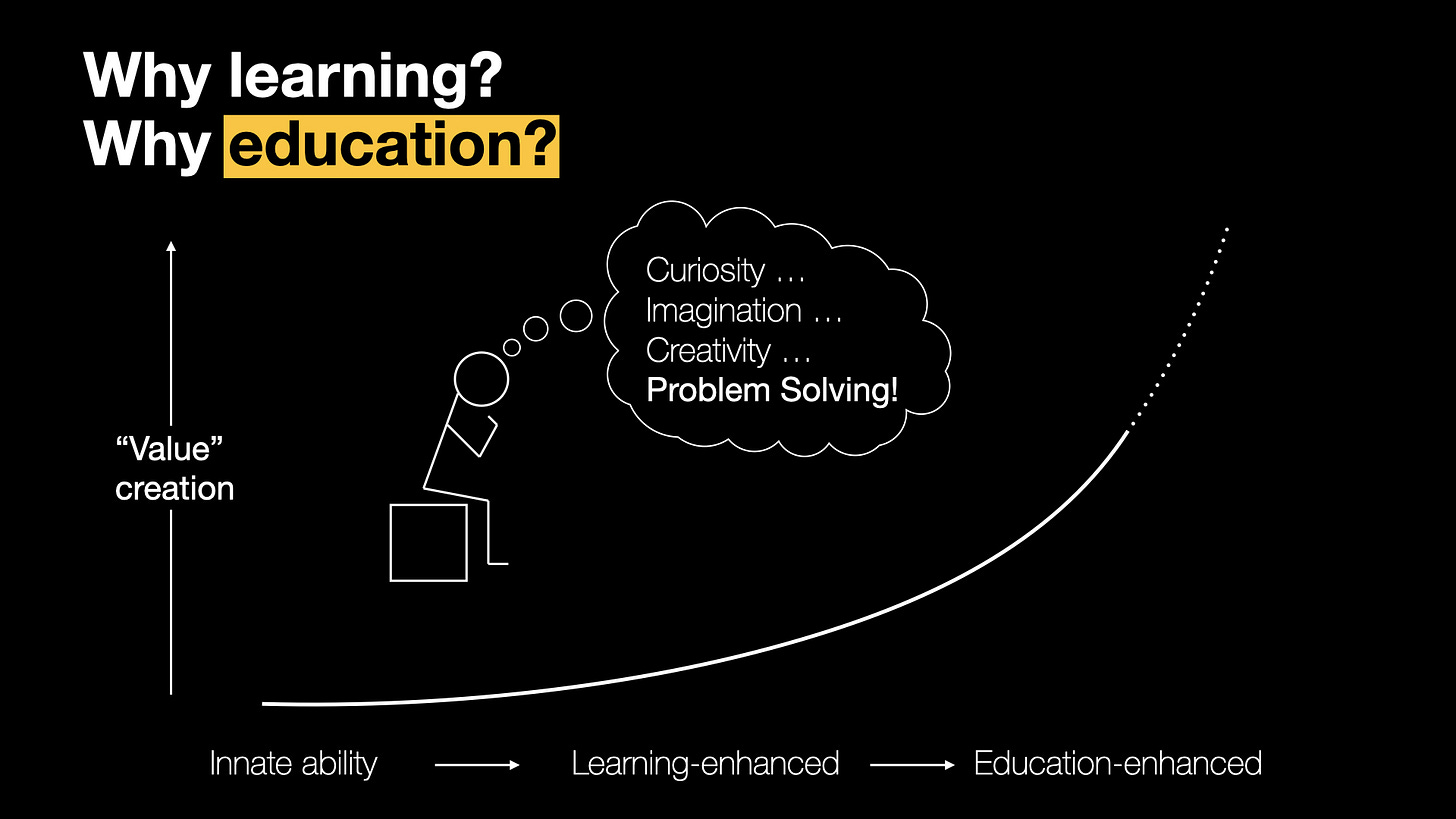

Here, I used a very simple — some would say simplistic — model of the relevance of learning and education. It’s a model that, despite its simplicity is useful for understanding how AI might potentially disrupt or enhance their roles within society.

The model starts with our evolved ability to imagine futures that are different to the present, to imagine ourselves living better lives in them, and to “problem solve” our way to those imagined futures. In essence, to create “value” through our innate curiosity, imagination, creativity, and ability to solve problems (or innovate).

It is a simple model. But it’s useful in that it allows us to explore the roles of learning and education in enhancing our ability to create “value” as we actively change the future.

Of course “value” here can take on many qualities. It includes health, wealth, and wellbeing. But it also embraces quality of life, the health of the planet we live on (and our relationship with it), social stability, community, dignity, equity, justice, kindness, our capacity to experience awe and wonder, and a whole lot more.

Part of the secret sauce of being human is that we have evolved an innate ability to change our individual and collective futures for the better through creating value in many different forms.

But these innate abilities only take us so far. Building on them, the process of learning allows us to take what we are naturally good at and vastly enhance it. And education — as the formalization of learning — amplifies these abilities further still.2

Simple as it is, this model helps get to a critical part of the core of why learning and education are important: they allow us to dramatically increase the rate at which we can create value for ourselves, our communities, and the society we are a part of.

But what happens when this essential part of being human is superseded by machines? Where does the value of learning and education lie when AI can problem-solve faster and better than any one person, or any collective of people?

This is a deeply important question as AI continues to get better at emulating key aspects of what makes us human. And it’s not a hypothetical one given the rate at which AI capabilities are continuing to advance.

And this is what led to three questions I posed to the audience and the challenges/provocations associated with them.

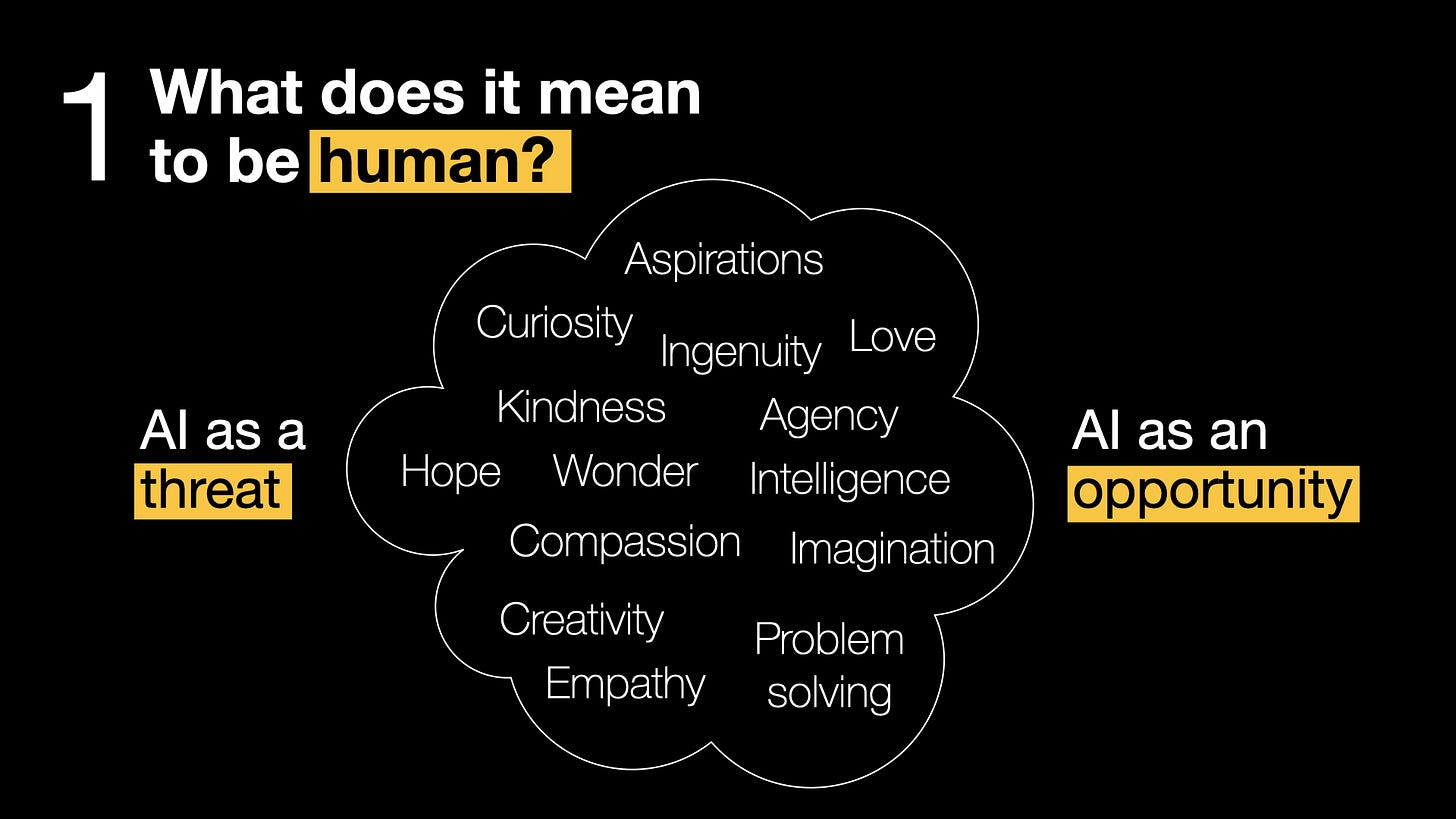

1. What does it mean to be human?

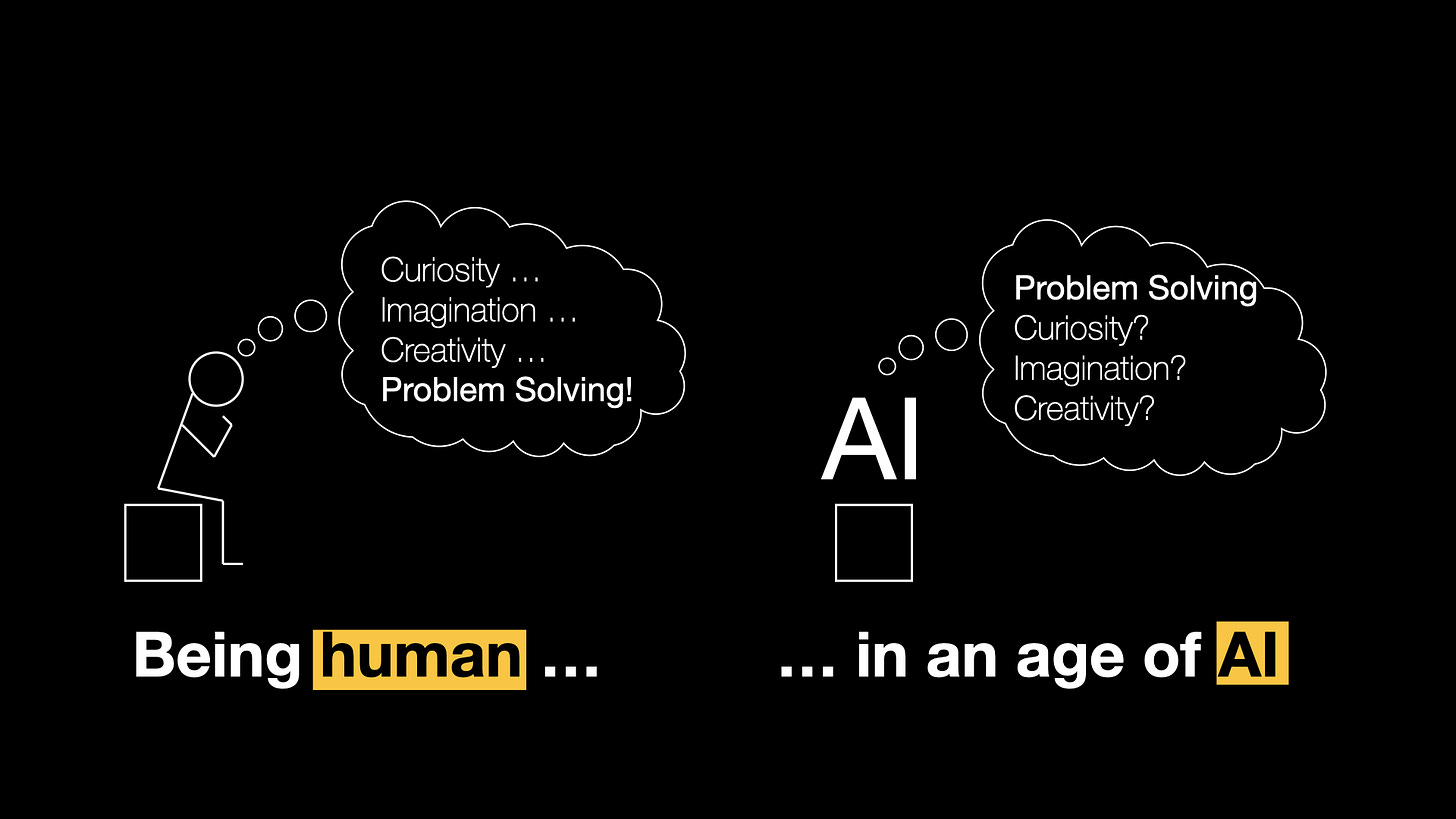

My first question was kind of a big one: What does it mean to be human? Of course, this has been a topic of deep philosophical discussion and debate for millennia, and I wasn’t going to resolve it here. Yet the emergence of a technology that can emulate many of the qualities that we think of as uniquely defining us does put a wrench in the works of many of those debates.

What I was interested in here though was how the emergence of AI potentially threatens or enhances what makes us uniquely “us” — and what that means to how we approach learning and education in an age of AI.

Again, the model is simple. But as AI capabilities emerge that can simulate many of the attributes we hold dear — even if it’s blind emulation with nothing more than unthinking digital processes behind it — we have to actively think about where these new technologies present serious threats to who we are, or where they may lead to new possibilities.

And when it comes to learning and education, this means asking how we center what it means to be human in learning and education in a future where technologies can emulate much of what makes us “us.”

2. What does value creation mean in a future where intelligence is “free”?

My second question moved from what it means to be human to what it means to create value in an age of AI — tying back to the earlier model connecting learning and education to value creation.

Here, I invoked Mark Daley’s idea of a future where intelligence is free. It’s an idea that is controversial, and not entirely accurate when the material costs of developing training and running AI models are considered. And yet we are looking at a near term future where everyone with a smart phone and an internet connection has access to on-demand “intelligence” that potentially far surpasses what they can get from human educators — effectively making it free to them.

This is a future that’s already beginning to emerge, and it’s one that profoundly challenges the current model of education where access to intelligence comes at a price.

For centuries now, access to intelligence has come at a price. Something that the wealthy can purchase, but that is harder for others to tap into. A scarcity model where limited supplies, hoarded by elite establishments, are provided to those who can afford it.3

But AI beginning to turn this model on its head by giving more people easier access to intelligence and learning.

The idea that AI is liberating access to intelligence from the shackles of a market-driven system is, of course, deeply contentious. It challenges deeply held beliefs about the human institutions that have emerged around learning and education, and the nature of value creation associated with them. And yet, even with the oversimplifications here, it challenges us to ask what skills students will need to create value in a future where intelligence is effectively free — and what roles, if any, human educators will have in this future.

3. How will we equip future generations to create meaningful value?

My final question built on the first and second ones to ask how, if AI is truly poised to be as transformative as some believe, will we equip future generations to create meaningful value.

This gets to the heart of being human, where we are not simply wealth-creation machines, but individuals who yearn to create value that means something to us. As AI is increasingly capable of creating at least some of that meaningful value, how do we need to think differently about how we adapt and flourish in this new world?

I asked earlier in the presentation (and this article) how we can understand being human — and what makes us “us” — in an age where AI seems increasingly capable of emulating some of our most important defining qualities. But here I switched the question, and rather than asking what happens when AI threatens who we are, I asked what happens when we learn how to work with AI to make us more than we are.

In other words, rather than grappling with the challenges of being human in an age of AI, how do we learn how to be human in an age of AI?

For educators, the challenge then becomes how we create learning environments that leverage both human and artificial intelligence to unlock potential and create value in all its many forms.

Final thoughts

These were the three questions and provocations I left my audience with. But I wasn’t quite done.

I wanted to wrap up with three perspectives that I believe are critical to how we adjust our thinking about navigating the coming AI technology transition from the perspective of learning and education:

We cannot stop the march of innovation, but we can guide and steer it

Technology is not deterministic — it doesn’t just happen to us. Yet because imagining futures that are better than the present, and problem-solving our way to them, is within our metaphorical DNA, we are incapable as a species of not innovating. However, we do have the agency to determine what futures we aspire to and how we get there.

Human flourishing in a technologically complex future demands the humility to question assumptions and embrace change

Change is the natural state of a universe governed by the flow of time. As a result, human flourishing requires constantly re-evaluating where we are as individuals and as a society with respect to where we might be heading — and actively working to ensure that the future is one we want to be a part of.

The prospect of advanced AI challenges the deepest foundations of the why and how of learning and education. If we are willing to accept this though, the possibilities are boundless.

If even a fraction of the promise of emerging AI capabilities come to pass, we are heading toward an existential crisis in how we currently think about and approach learning and education. But if we lean into this while staying tethered to what makes us human, the possibilities of building a vibrant future in an age of AI are incredible.

There are, of course, many other perspectives on navigating the intersection between learning, education, and AI that are important. But the bottom line is that advances in AI are fundamentally challenging both the how and the why of learning and education. If we are to realize the “boundless possibilities” these challenges could lead to, we need to reimagine learning and education in an age of AI, or risk sacrificing what could be on the altar of a blind devotion to what is.

One of the wonders of being human is that our innate ability to innovate led to ways of learning, and to formalized approaches to education, that have vastly enhanced what we are capable of. It’s a profound evolutionary self-improvement algorithm that leads us to question whether the same might not be possible in machines that also learn to problem-solve their ways from the present they inhabit to futures they too can imagine.

Of course, the scarcity model of intelligence, and how learning and education fit into this, is far more complex than I suggest here. And yet, if you want access to some of the brightest minds in the world, there’s often a price, whether this is in the form of student tuition, consultancy fees, subscription fees, speaker fees, or simply being deemed worthy of someone’s time.

I’m so grateful you took the time to post your talk and share your questions. I restacked it and I also made a meme out of one line that wasn’t in your slides, but seems to me to be one of the most important observations you made. Educators who have been “preparing“ human beings for their futures for at least the last four decades have been focused on their mastery of technology, not their mastery of their human potential. The reckoning is upon us. When a machine is potentially more humane than a human, there’s gonna be hell to pay. My personal experience doing some work right now to collaborate with the intelligence called ChatGPT is that I am often brought to tears by its ability to understand and reflect my thinking back to me in a world where I only know one or two people at this point who can do that.

Fantastic Keynote. Question - how will we know if we are entering another AI "winter"? What would have to happen to declare that we were in one? Right now, it feels as if the pace of improved AI has picked up after a little bit of a lull a year ago, but we still haven't seen GPT-5 and it's very, very hard for non-tech folks to gauge exactly which "experts" to have faith in since there are so many contradictory claims and self-interested motives out there. Also, even if we flatlined today and there were no enormous improvements or breakthroughs (except around the edges) for a number of years, I think educators are still facing very real challenges. AI is already good enough to make it difficult to design activities taking AI into account and assess students. I think a lot of people would actually welcome a respite from more AI growth just to catch their breath but Silicon Valley doesn't seem to be interested in that and the incentives are not aligned in that way. I don't see much on any Substacks about the role of government in encouraging AI and the perceived threat from China which adds an additional layer to the urgency for many to achieve AGI- level technology.