Navigating the challenges and opportunities of technologies that "stop biological time"

A groundbreaking new collection of papers in the Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics explores the ethical, legal and policy challenges of advanced biopreservation technologies

Imagine it was possible to extend the time between a donor heart becoming available and a transplant patient receiving it from hours to days — or even weeks. Or what if we had the technology to preserve donated kidneys so they’re available for transplant when needed rather than when available.

More broadly, what if we could make transformational leaps in technologies that slow — or even stop — “biological time,” allowing living biological materials from almost any source to be preserved and then “resuscitated” as needed.

If we could it would be a game changer. But it would also raise a mountain of ethical and social challenges that stand between what these technologies are capable of, and their successful and beneficial use.

It’s this complex risk landscape around emerging biopreservation technologies and their successful and beneficial use that a new paper in the Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics addresses — one of a number in the same issue of the journal on the ethical, legal and policy challenges of advanced biopreservation technologies.

A few years ago I became involved with a National Science Foundation Engineering Research Center that set out to “stop biological time” by radically extending the ability to bank and transport cells, aquatic embryos, tissue, skin, whole organs, microphysiological systems, and even whole organs — ATP-Bio, or Advanced Biopreservation Technologies for the Preservation of Biological Systems,

One of the five pillars of ATP-Bio — the one that I’m engaged with — focuses on ethics and public policy. And this week we published a ground breaking collection of papers on the ethical, legal and policy challenges surrounding the technologies that the initiative is developing.

It may seem a little counterintuitive for a multi-million dollar initiative focused on developing commercially viable new technologies to be considering such challenges. But from the get-go, the leaders of ATP-Bio realized that the technologies they were working on were potentially so transformative and disruptive that ignoring the social landscape which they would emerge into would be tantamount to setting themselves up for failure.

More than this though, there was a deep realization that these are technologies designed to save and improve lives — and that ignoring potential ethical, legal and policy challenges would negate the very reason why members of the engineering research center were doing this in the first place.

This is why ethics and policy are a core component of ATP-Bio. And it’s this group — which includes transplant surgeons and lab researchers as well as social scientists, bioethicists and policy experts — that was responsible for the just-published collection of papers in the Journal of Law, Ethics and Medicine on “Emerging Technologies to Stop Biological Time: The Ethical, Legal & Policy Challenges of Advanced Biopreservation”.

My primary contribution to this collection was a co-authored paper on using our “risk innovation” framework to explore the risk landscape around advanced biopreservation technologies. But before I get to that paper, it’s worth looking more closely at why the conversation around risk and responsible innovation is such an important one here.

In their introduction to the collection of papers, guest editors Susan Wolf, Tim Pruett and Korkut Uygun emphasize that “Human beings depend on biological materials for survival — everything from food to medical interventions such as organ transplantation, to the environments in which we live” and that “The 21st century is now seeing an explosion of interest in new techniques for biopreservation” where “supercooling, partial freezing, vitrification, and nanowarming are among the techniques showing remarkable promise in a range of biological materials, from cells to tissues, whole organs, and even whole organisms.”

In the following multi-author framing paper we further re-enforce this, stating that “emerging technologies for prolonged biopreservation have the potential to radically alter practices in the biomedical and life sciences ranging from environmental conservation to health care.” (This paper also outlines the technologies that ATP-Bio is exploring, and why they matter).

We go on to note that “US authorities and stakeholders are not prepared to oversee the new wave of biopreservation technologies” and that naively introducing seemingly-beneficial but highly disruptive biopreservation technologies could do more harm than good if we’re not careful.

Here, potential pitfalls include everything from disrupted donor organ supply chains and ecosystems, to poorly regulated tissue and organ markets, to the emergence of dual use technologies that flip biopreservation technologies from supporting human wellbeing to harming it (biopreserved pathogens for instance).

Part of the challenge of ensuring advanced biopreservation technologies are developed and used beneficially and responsibly is the “pacing problem,” where emerging science outpaces the development of law, policy, and other governance mechanisms. Oversight approaches to emerging technologies are discussed at length in the collection’s framing paper, drawing substantially on the work of Gary Marchant (also one of the co-authors). Yet developing effective oversight mechanisms is only part of the highly complex landscape between emerging capabilities in this area and their socially beneficial use. And this is where our risk innovation paper comes in.

In exploring the broader challenges of ensuring the emergence of beneficial and responsible technologies from ATP-Bio, we were interested in whether we could apply our work on navigating a range of more subjective and often-ignored risks to advanced biopreservation technologies.

Some years ago my colleagues and I developed the idea of “Risk Innovation” — a way of bringing an innovation mindset to understanding and navigating the types of risks that are often ignored but have a tendency to bit hard in a world dominated by rapidly advancing technological capabilities.

Our early work led to the Risk Innovation Nexus: a set of tools and resources primarily aimed at startups to raise awareness around the types of risks — often social, ethical, and governance-related risks — that well-meaning but time and resource-constrained founders had a tendency to overlook; often at their peril.

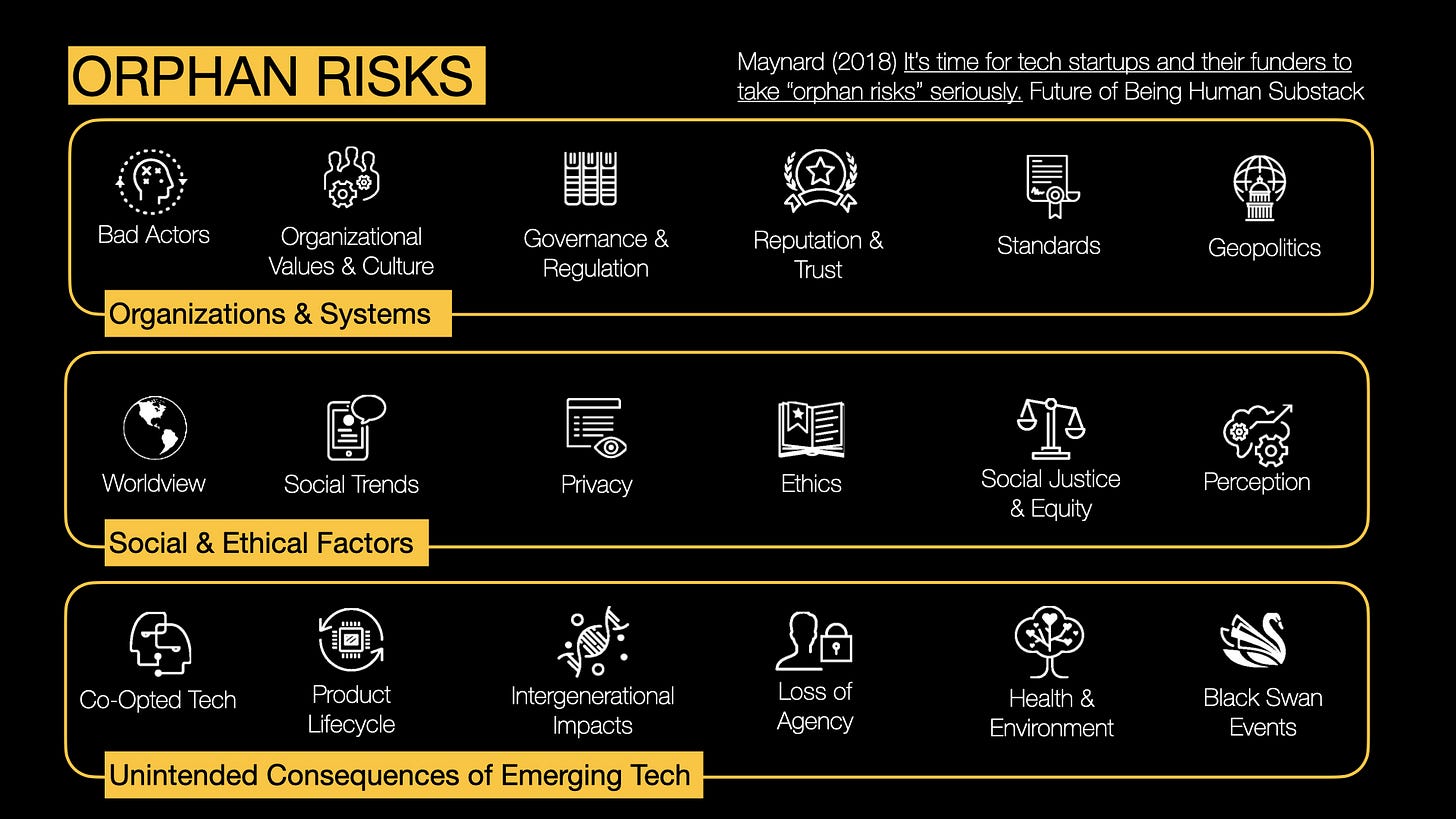

At the heart of the Risk Innovation approach is a list of eighteen “orphan risks” that are hard to quantify, easy to ignore, yet potentially devastating to an initiative if not considered. These are coupled with an understanding of risk as a “threat to value”, including where an initiative threatens value for key stakeholders and this, in turn, becomes a secondary threat to value to the initiative.

In the case of ATP-Bio, we wanted to see if our approach could be extended to an interdisciplinary and multi-sector consortium involved in developing and commercializing advanced biopreservation technologies — and this was the driver behind the paper “Successfully Bridging Innovation and Application: Exploring the Utility of a Risk Innovation Approach in the NSF Engineering Research Center for Advanced Biopreservation Technologies (ATP-Bio)” (co-authored with Ken Oye from MIT, my ASU colleague Marissa Scragg, and Tim Tripp and Susan Wolf from the University of Minnesota).

Despite the long-winded title, the paper’s worth reading in full as it maps out a pragmatic approach to both developing new technologies responsibly and beneficially — especially within multi-million dollar and multi-stakeholder initiatives such as the National Science Foundation Engineering Research Centers.

But as I also gave a talk on the paper a few weeks ago, I thought it might also be helpful to provide a summary based on that presentation:

Advanced Biopreservation and Risk Innovation — the quick(er) version

(The following slides are part of a presentation sponsored by the Ethics & Public Policy pillar of ATP-Bio on October 8 2024. They draw on the paper Maynard AD, Oye KA, Scragg M, Tripp T, Wolf SM. Successfully Bridging Innovation and Application: Exploring the Utility of a Risk Innovation Approach in the NSF Engineering Research Center for Advanced Biopreservation Technologies (ATP-Bio). Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2024;52(3):553-569. doi:10.1017/jme.2024.126)

The ATP-Bio Engineering Research Center focuses on advanced biopreservation technologies across three domains: Human health, food systems, and biodiversity. In each there is significant potential value to society associated with emerging biopreservation technologies. But there are also complex threats to realizing this value.

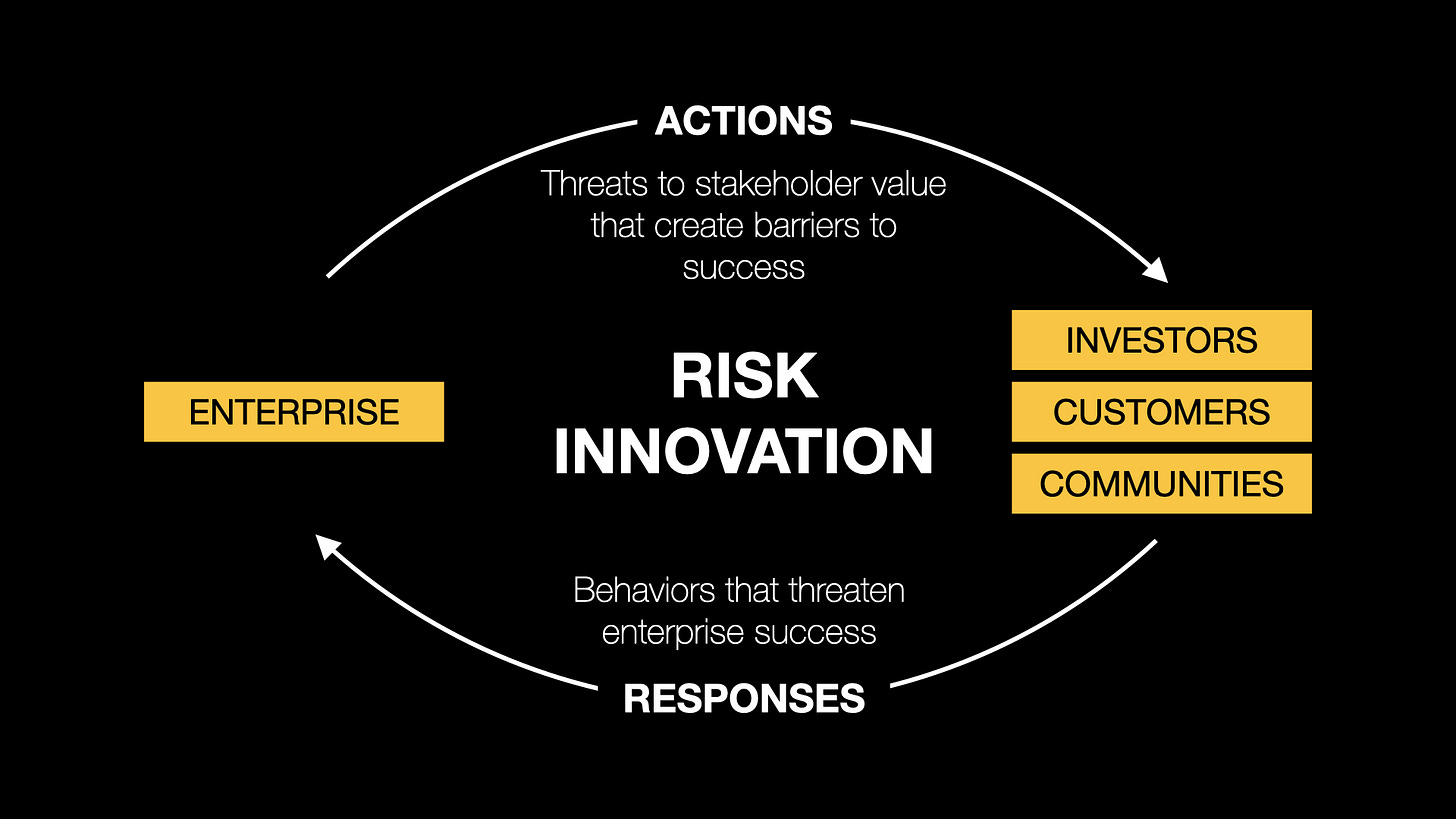

One potential way to understand and navigate these threats (which will depend on how “value” is defined by different organizations and communities) is to reframe risk as a “threat to value” — whether this threat is to the creation of new value, or a threat to existing value.

This framing is foundational to Risk Innovation, which explores novel ways of protecting and growing value.

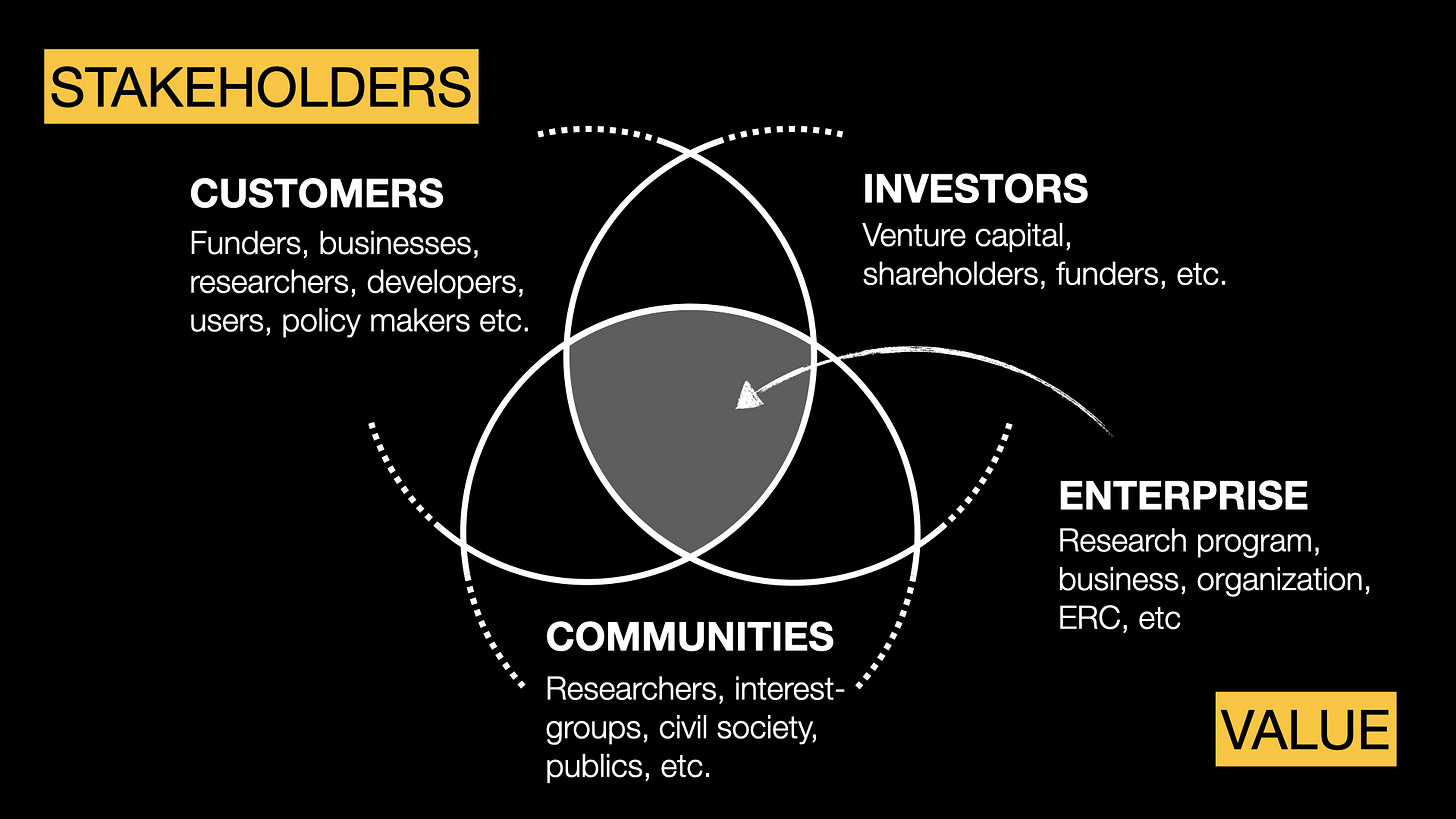

At the center of the Risk Innovation approach is the “enterprise” — which may be a startup, a for-profit, a not for profit, a government agency, a research group, a large research consortium, or any other organization focused on creating value. Surrounding this are three broad stakeholder groups loosely classified as investors, customers and communities — although these are not fixed.

Importantly the Risk Innovation approach focuses on value rather than values — the latter are important, but the former is more effectively operationalized in policy and decision-making.

Within this framework, it becomes possible to start exploring threats to value for the enterprise and the stakeholders — and both are intertwined here — including threats to existing value and threats to aspirational value.

Conceptually, this leads to the concept of a risk landscape that lies between where an enterprise currently is, and where it wants to end up. This landscape includes risks that can often be handled using existing tools — including quantifiable risks to human, environmental, and fiscal health. But it also includes risks that are often overlooked because they’re messy, subjective, and hard to deal with — we refer to them as “orphan risks”.

This framework was initially developed for working with startups. Early on we gave ourselves the goal of developing a tool that would be useful to a time- and money-constrained CEO of a startup. This led to a Risk Innovation Planner that was intended to take 30 minutes to complete and help reveal new ways of thinking about risks and opportunities (we almost nailed it), and a suite of resources that were are available for anyone to use.

But we didn’t know whether this framework, or the tools and resources we developed, would translate over to a multidisciplinary and multi-sector initiative — which is why we embarked on this study.

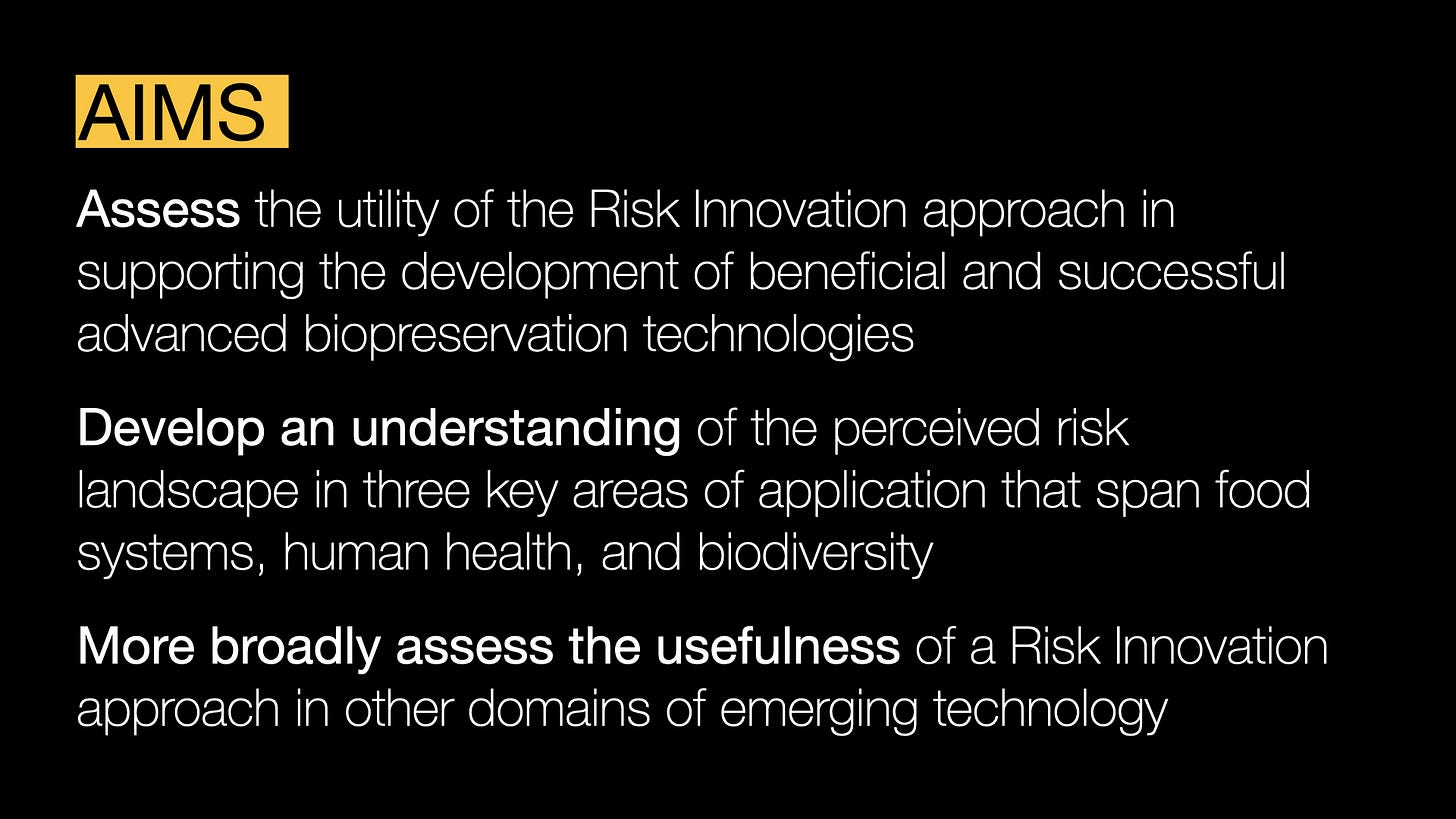

In the study we set out with three aims: assessing the utility of the Risk Innovation approach in supporting the development of beneficial and successful advanced biopreservation technologies; developing an understanding of the perceived risk landscape in three key areas of application that span food systems, human health, and biodiversity; and more broadly assessing the usefulness of a Risk Innovation approach in other domains of emerging technology.

Our approach was to draw on the expertise of ATP-Bio partners across three 90-minute (and IRB-approved) workshops that took participants through a modified Risk Innovation process.

Each workshop focused on one of the three domains of ATP-Bio (human health, food systems, and biodiversity), and resulted in participants identifying key stakeholders, key areas of stakeholder value, and orphan risks of potential importance.

The process was subjective and was aimed at getting a broad sense of perceived areas of value and threats as well as assessing the utility of the approach. And participant numbers were relatively low — 17 in all. But the workshops led to a wealth of insights into potential hurdles to developing beneficial and responsible advanced biopreservation technologies.

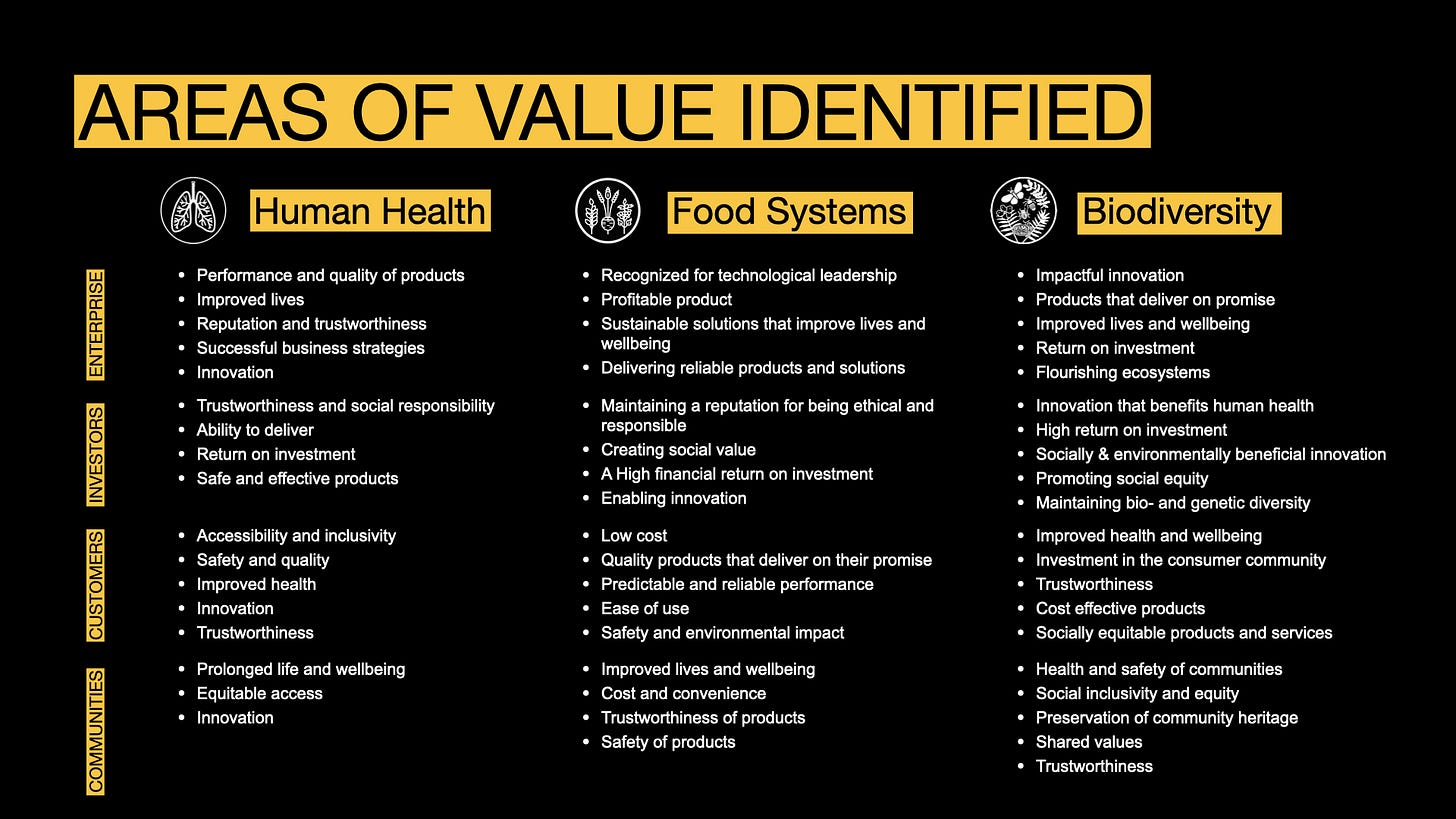

Starting with areas of value, we identified over 50 potential areas across all thee domains and stakeholder groups. These were synthesized from participant input and clustered where appropriate, and should not be considered as robust or authoritative. Yet they do provide a glimpse into areas that developers of advanced biopreservation technologies should probably have on their radars.

They also begin to show us how different domains and stakeholder groups were perceived to align with different areas of value.

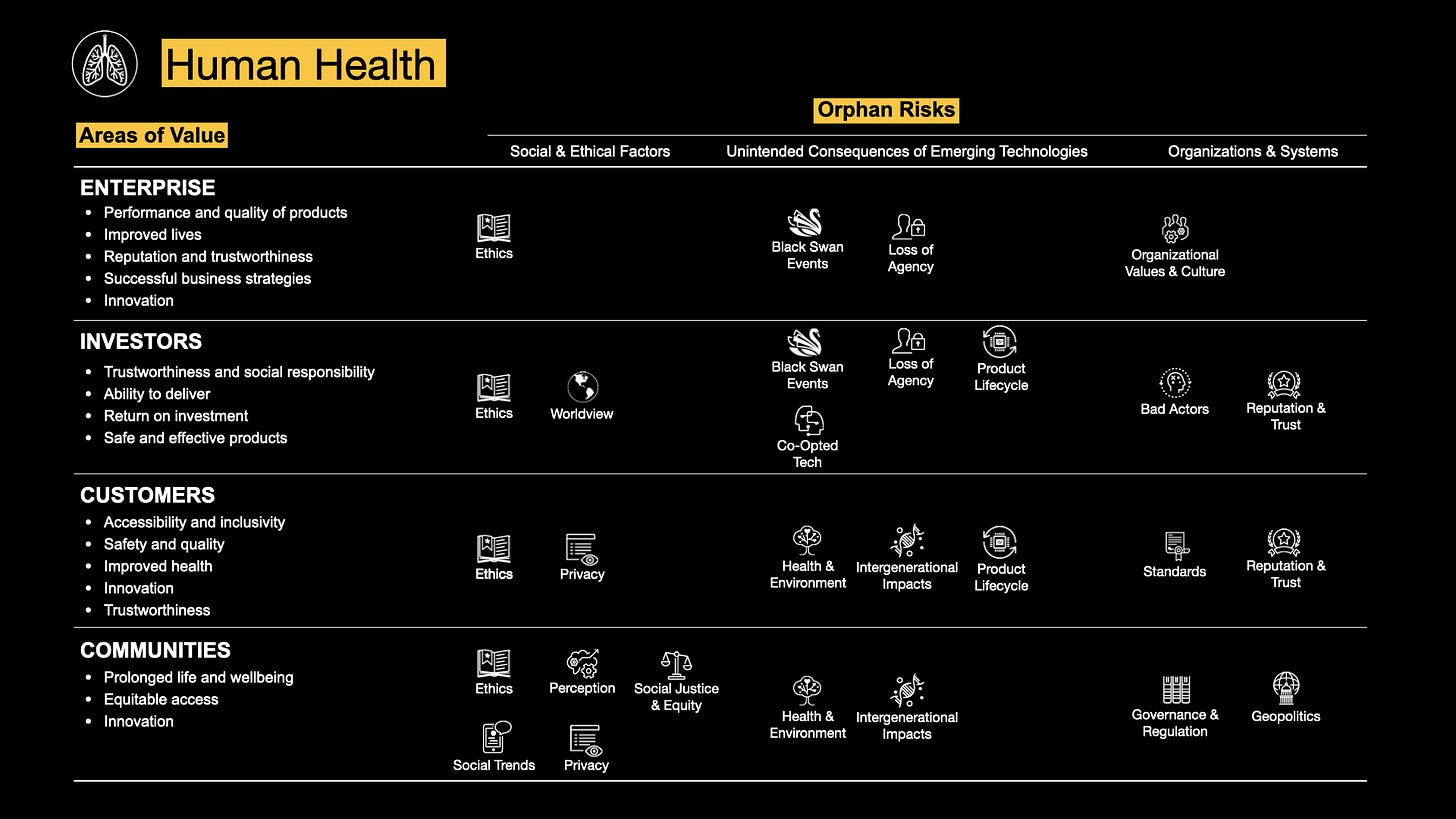

We then pulled out the more prominent orphan risks that participants associated with each stakeholder group. Part of the Risk Innovation process involves visually capturing a perceived or subjective association between key areas of value and key orphan risks, and this is shown in the “Risk Innovation Landscape” below for advanced biopreservation technologies and human health (similar maps were made for food systems and biodiversity).

These maps allow a visual representation of orphan risks which are directly associated with an organization’s actions (internal threats), and those that arise from an organization threatening value associated with key stakeholders in ways which lead, in turn, to a threat to value to the organization (reciprocal threats).

Sticking with the human health domain, this assessment allowed us to identify which orphan risks were perceived as being more important or relevant in a particular domain. Again, the slide below is from the human health domain, but similar analyses were carries out for the other two domains:

Pulling all of this together, we provided an assessment of the relative weights that were placed on different orphan risks across all three advanced biopreservation technologies domains:

This plot is dense and subjective — there’s no data here that can be taken as repeatable or absolutely representing reality. What it does do though is give a good sense of how participants understood the relative importance of different orphan risks across the three domains — as well as all the domains combined. And as all participants brought considerable expertise to the table, it presents a snapshot of their perceptions that’s worth paying attention to.

Looking through the data — and remembering the qualifier that these are subjective — it’s interesting to see the dominance of ethics, perception and government & regulation across all three domains. This wasn’t surprising to me as much of my work focuses on emphasizing the importance of orphan risks like these in undermining progress and value creation if not taken seriously. But it was surprising to see these emphasized by experts and practitioners who may otherwise not fully understand how damaging ignoring them can be.

It’s also interesting to observe orphan risks where there seemed to be a marked divergence between domains — including privacy, co-opted tech (where a potentially useful technology is harmed by uses that undermine it in the eyes of investors, users and others), and bad actors (researchers and companies that give the technology a bad name).

There’s more in the paper, but a key takeaway from the study was that the process raises awareness of factors that may otherwise be overlooked in the development of a new technology (advanced biopreservation technologies in this case), and allows researchers and innovators to increase their chances of success by identifying and navigating around potential roadblocks early on.

Of course more work is needed — there always is. But from our findings it seems likely that a Risk Innovation approach can be used as an important tool in helping ensure the societal benefits of transformative new technologies — not necessarily by impressing on researchers and developers the need to “do the right thing”, but by making it clear that their success is intimately intertwined with how they impact (and threaten what of value to) others around them; and how, in turn, the responses and actions of others potentially impact them.

The full collection of papers can be accessed for free at Emerging Technologies to Stop Biological Time: The Ethical, Legal & Policy Challenges of Advanced Biopreservation. Volume 52, Issue 3 of the Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics. Fall 2024. I’d highly recommend reading them!

Oh my that was a great read, first thing in my morning. Jotted down my thoughts and finally commenting.

Though i haven't read the links mentioned, but the thoughts that came to my mind (among many) were:

A cultural shift where we focus on "fixes" rather than the holistic preventions. When it comes to transformative tech, feels like a recurring pattern

Legal frameworks around consent and ownership across multiple generations . Like who holds the rights to biological materials or maybe preserved data in decades ahead

Weaponization of these technologies and adaptable policy frameworks around them, while balancing innovation too

I hope no one makes an "NFT" around it 😅