Massive new study reveals new insights into UBI

The OpenResearch Unconditional Cash Study – the largest of its kind in the US – has just released its first round of findings. The results are inconclusive, but insightful nevertheless

Back in January 2020 a massive study into the potential impacts of providing people with an unconditional basic income was proposed. Led by the organization OpenResearch, the idea was to give 1000 low-income participants $1000 a month over three years, and use the data to explore how providing people with a universal basic income, or UBI, might positively impact their lives and society more broadly.

The first results from the study have just been released, and they are well worth a deep dive.

More than anything the results highlight just how complex finding a strong association between UBI and positive outcomes is. Despite this though, there are important insights arising from the research that are likely to fuel further thinking around unconditional cash transfers (giving people money with no strings attached) — especially as AI and other technologies disrupt conventional ways of earning an income.

The OpenAI Unconditional Cash Study

UBI has been a hot topic for some time now. The idea is simple — by providing everyone with a basic income you give them the means to overcome poverty traps, the agency to pursue life-enhancing possibilities, and the ability to create value in a world where technology and automation are threatening conventional jobs.

And yet it’s proven exceptionally difficult to devise and run studies that demonstrate clear causal associations between providing people with unconditional cash, and beneficial outcomes.

The OpenResearch study — with substantial financial support from OpenAI’s CEO Sam Altman — set out to “take a holistic approach to understanding the individual-level effects of sustained unconditional cash assistance to create data that can be broadly applied to help policy makers and academics improve the effectiveness and efficiency of future social policies and programs.”

The result was a three year study, supported by a team of university-based academics, that recruited 3000 people for a 3-year study and randomly assigned 1000 of them to receive $1000 a month over the study period, and 2000 of them (the control group) to receive $50 per month over the same period.

Participants were surveyed (and assessed) on a number of indicators of social, personal and economic wellbeing over the course of the study. These data were also augmented by personal interviews with a small group of participants.

A few days ago, OpenResearch released a top level assessment of the study’s key findings in the areas of employment, health, entrepreneurship, agency, mobility (moving house and neighborhood), and spending. They also released 39 personal stories from participants.

In addition, two academic working papers from the study were published (with a third on the way), and it’s these that I want to start with here.

Academic Papers

The two papers address associations between unconditional cash transfers and health, and guaranteed income and employment. Both were conducted under the auspices of the National Bureau of Economic Research. And while neither has been peer reviewed as yet, both of them are rigorous in the research conducted and the analysis undertaken.

The statistically significant associations that each study found between the $1000 a month cash transfers and measurable outcomes were, it’s fair to say, limited and tenuous. And this underlines just how hard it is to tease out robust insights from such studies.

But both studies are nonetheless important in how they extend the evidence-based baseline for UBI research. And they do hint at a number of underlying trends and associations that are relevant to future research and decision-making around UBI.

Health Study

Starting with the health study, researchers found that the $1000 per months led to an initial increase in food security and a lowering of stress amongst participants, but that these effects diminished over the three years.

There were also indications that participants spent more money on heath care over the study, indicating that they had more agency over looking after their health.

That said, there was no indication of improvements in physical health over the three years, or indicators of increases in healthy behaviors such as physical activity or sleep.

Looking through the data, this lack of clear correlations between payments and health indicators is likely as much to do with the challenge of finding small signals in noisy data as it is to do with a lack of real-world effects — something that illustrates just how hard studies like this are. This also raises questions around what the appropriate indicators of health are in such a study, and whether any inferences drawn are associated more with what was measured than what was affected.

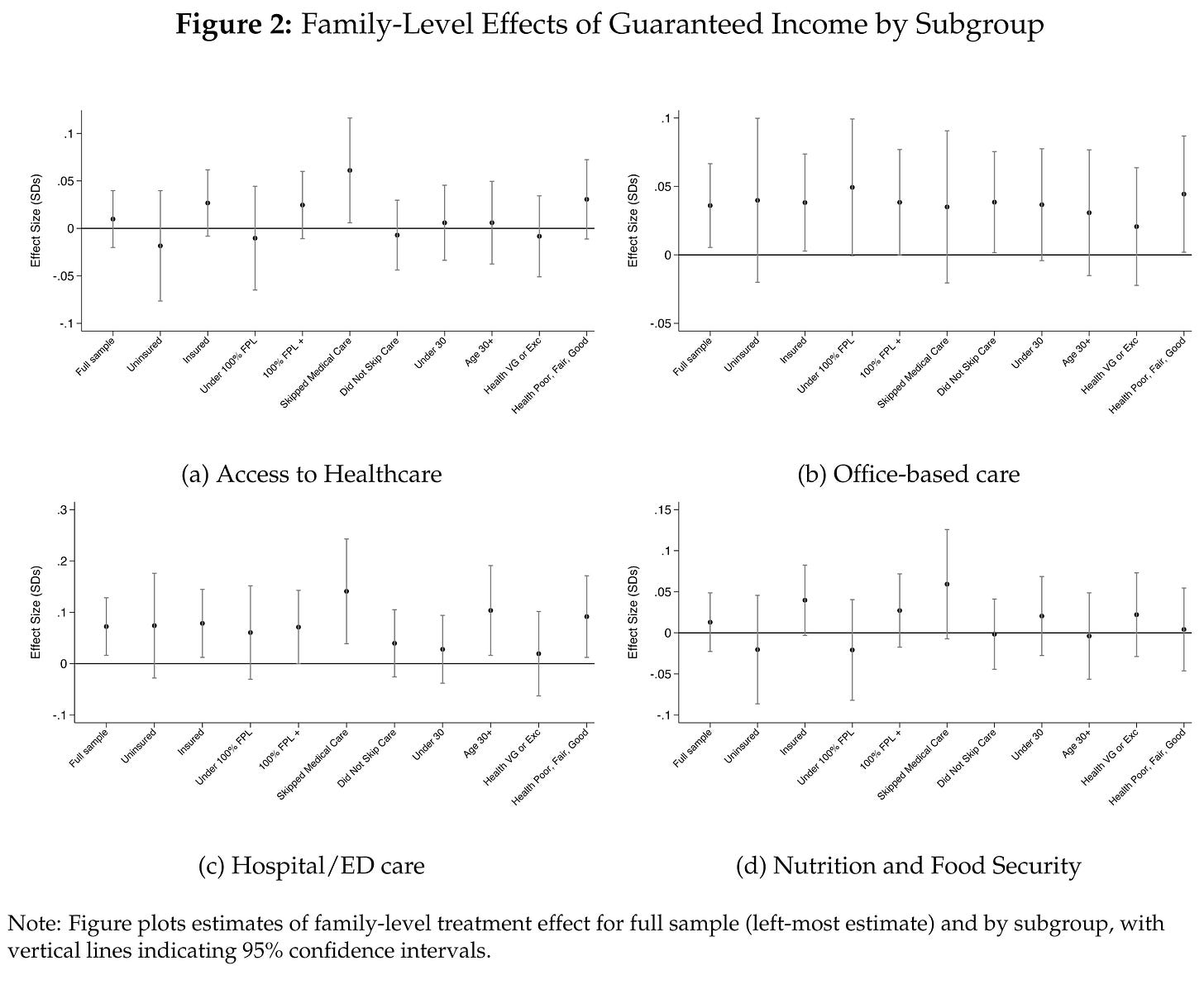

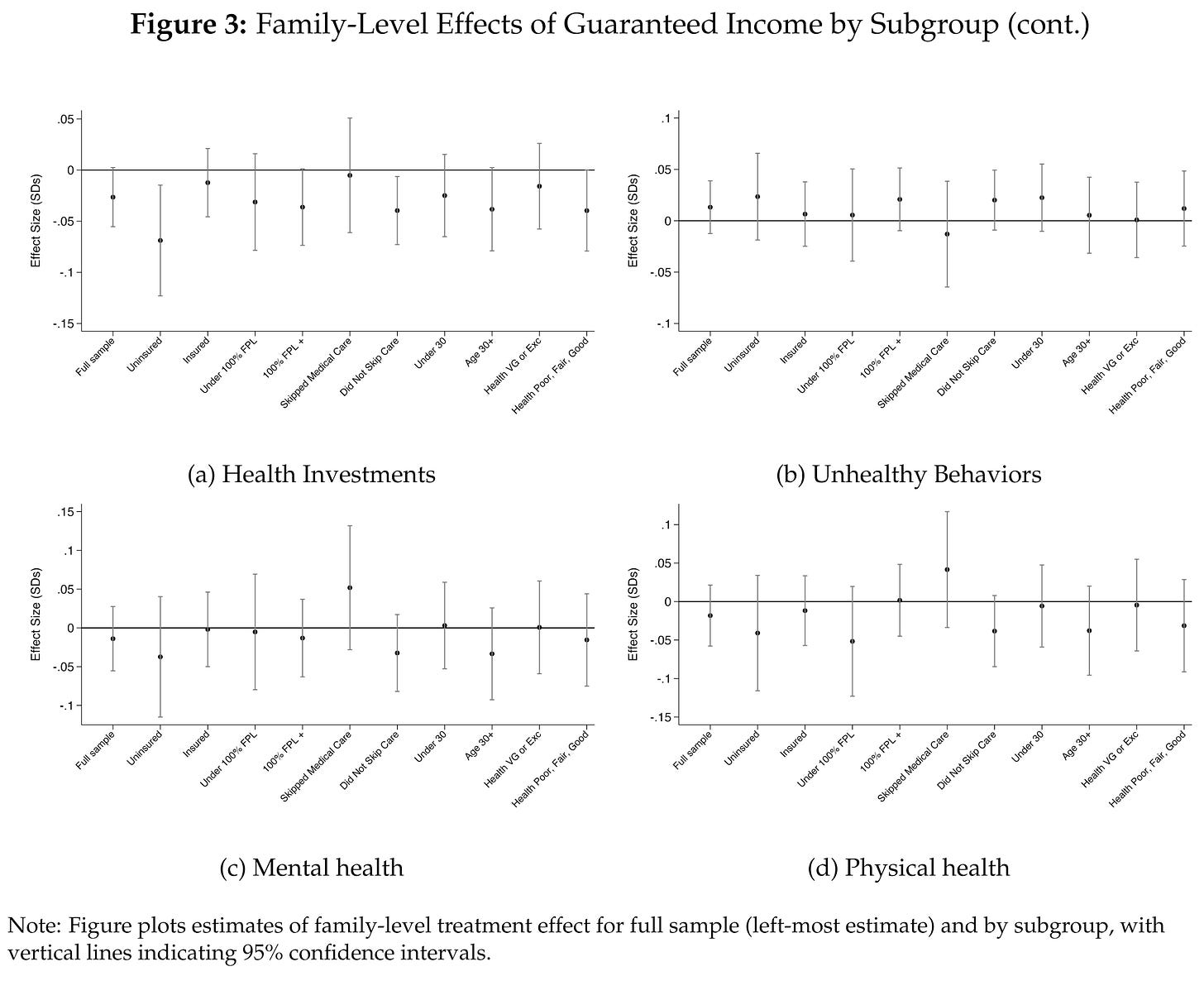

This is seen below in figures 2 and 3 from the paper that consider health related indicators as a function of different study sub-groups.

While it’s tempting to infer effects, it can clearly be seen in these figures that the variance within groups makes determining whether effects are real or not is statistically challenging in most cases.

As the authors conclude, “The appeal of cash transfers lies in the freedom that they give beneficiaries to make their own choices about what type of consumption to prioritize. However, the nature of that freedom means that cash transfers are a blunt instrument for improving health and reducing health disparities specifically.”

Importantly they also note that “the lack of an effect of the transfers on physical or mental health does not imply that the cash transfer program was unsuccessful at achieving other important goals, or that the transfers did not increase welfare for recipients.”

Here, they cite the companion employment study paper (see below) and an as-yet unpublished paper on consumption that show that participants “consumed more leisure, food, housing, transportation, and goods and services as a result of being randomly assigned to the high cash transfer arm.” And they underline that, while these choices did not appear to directly affect the health of participants, they did allow them “to increase consumption in ways that the participants valued most, as revealed by their own choices.”

Employment Study

The employment study is, if anything, broader in scope than the health study. But also more revealing. This study focused on teasing out causal associations between unconditional cash transfers and a wide range of employment-based outcomes.

Interestingly, the group receiving $1000 per month (equivalent to $12,000 per year) showed an overall relative drop in income from other sources by $1500 per year on average. Participants also worked less on average compared to the control group by 1.2 - 1.4 hours per week, while spending more time on leisure.

These are relatively small effects, which again underlines just how hard it is to find substantial causal relationships in studies like this. And it’s important to note that participants in the $1000 per month group were financially better off than the control group despite the drop in income outside of the cash transfers. But the results do indicate that participants receiving $1000 per month felt less need to be part of the grind of working every hour to make a living — remembering that they were all from low-income groups entering study.

The results did not indicate any changes in quality of employment associated within the $1000 per month group. However, there were indications that recipients showed more of an entrepreneurial orientation or intention — suggesting possible longer term impacts from the cash transfers.

That said, over the course of the study there was no significant observed increase in entrepreneurial activity.

The study’s authors conclude that “participants in our study reduced their labor supply because they placed a high value, at the margin, on additional leisure. While decreased labor market participation is generally characterized negatively, policymakers should take into account the fact that recipients have demonstrated–by their own choices–that time away from work is something they prize highly.”

This is an important insight as it indicates that workers in the US — especially amongst those in low-income groups — are being pushed to work harder than they want, and that unconditional cash transfers empower people to have more agency over their lives, even if this doesn’t necessarily lead to clear health benefits.

OpenResearch’s Initial Assessment

While these two academic studies indicate few statistically significant associations between the $1000 unconditional gifts and specific impact metrics, the more qualitative initial assessment by OpenResearch paints a more positive picture — especially with respect to agency.

The OpenResearch study website has a wealth of information, data and analysis on the study — and is well worth talking time to explore and digest this. But it’s the findings on agency and the participant stories that particularly stood out to me here.

Agency

In their analysis, OpenResearch staff found that the unconditional cash transfers allowed people to, in the words of one participant, “Dream bigger. Do more. Consider more.”

Overall they found that receiving the $1000 per month had a positive and significant impact on how participants budgeted and planned for the future, their aspirations to pursue further education, and their interest in entrepreneurship.

Interestingly, the effect was greatest for recipients who had the lowest household income at enrollment, where “individuals were, on average, 34% more likely to have participated in education or job training during the third year of the program compared to control participants.”

Unlike the academic studies, these insights from OpenResearch are provided with numbers but with little supporting data or analysis. As a result, I’m treating them with a grain of salt — especially as they strongly support what OpenResearch set out to show.

This is not a criticism of the study or the organization and its staff, and I’m sure that the analyses and the underlying data are solid. It’s simply that, when an organization is committed to showing certain outcomes, it’s very hard not to put a positive spin on ambiguous data, or data that are suggestive but not statistically robust.

This is why the associated academic studies are so important, and likely why they are more measured in their analysis.

That said, it’s exciting to see at least a glimmer of an association between unconditional cash transfers and positive impacts which, while hard to quantify, are nevertheless important.

Participant Stories

This excitement spills over to the participant stories that are associated with the study.

Of course, anecdotes need to be treated with extreme caution in a study like this. It’s easy to cherry-pick accounts that indicate positive impacts while minimizing those that don’t. And even with the best of intentions, we all tend to read our own biases into personal accounts that blinker us to a more analytical assessment.

That said, in a study like this where — even at this scale — it’s hard to extract causal relationships from the data, where quantitative analysis is messy, and where it’s not even clear whether the right questions are being asked, qualitative assessments can be extremely insightful —to the extent that they invoke the saying often attributed to Einstein that “not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.”

Out of the 1000 participants, there are currently 39 participant stories (a mere 3.9% of study participants). But they are compelling.

A mix of audio recordings and written summaries, they capture just how transformative the payments were on a personal level. And importantly, they contextualize and humanize participants in ways that transcend just looking at the aggregated data.

For instance, from one participant:

After her fiancé was murdered, she moved in with the grandparents of her two oldest children. “I knew my ultimate goal was I’m leaving here”. She took the unconditional cash and opened a security credit card to start building her credit. Every month, she put half of the money into her savings account. She was able to use the money to build her credit score, move out into her own apartment, and help pay for her children’s graduation and college expenses. “Both my kids started going to college, we didn't have a financial struggle, in a sense. We didn't have to struggle financially. With that extra $1,000 a month, it helped so much on just senior pictures, or hey mom, I wanna go so-and-so with my friends. It was the supplemental income, as if I had a helper. It really was my help mate.”

And from another:

Kyle (not his real name) is a father of three. The children's mother struggles with mental health and substance abuse issues, and he handles the majority of parenting responsibilities. In 2017, Kyle suffered a back injury which required surgery and left him unemployed for over 2 years. During this time, he got buried in debt. When he first learned about the unconditional cash, his main goal was to stop the constant calls from collectors. He felt a pressure to get out of the hole. “I could finally stop the creditor calls all day every day…you know just alleviate some of that day-to-day, constant agony of phone call after phone call…sometimes you just have more months than money.” He had been thinking about getting a second job to pay off the debt but was worried about affording childcare. “I can't afford to pay somebody to watch my kids while I go make 5 or $10 an hour. It just doesn't make sense if I'm paying $40 an hour for childcare.”

The $1,000 a month made it so he didn’t have to work two jobs, and he could spend more time with his children.

And this audio recording from a participant struggling with addiction and living with her grandparents in a neighborhood that exacerbated the problem:

When the program started, Zoe (not her real name) was at a pivotal moment in her life. After a domestic dispute with her husband, her kids were taken into Child Protective Services (CPS). She was struggling with addiction and living with her grandparents in a neighborhood that exacerbated the problem.

Then, Zoe used the money to move into a women’s sober house, and while there, was able to get her children back. Now, Zoe has a much better relationship with her husband and children. She is living with her family in a new state, in a place she describes as safe and spacious and closer to family support and good schools for her children. [Listen to Zoe’s story]

These stories aren’t quantitative evidence. But they open a window into the lives of people who were transformed by the $1000 payments in ways that had a profound impact, and yet are fiendishly difficult to capture through data.

And this to me underlines perhaps one of the most important takeaways from the study so far: That even payments as low as $1000 per month seem to give people the opportunity to take a few more steps toward carving out a life that has more meaning and value to them personally — and to a future where they are more likely to flourish — even though this is still hard to capture quantitatively.

Final Thoughts

There are, of course, a lot of questions left hanging by the study. But I fully expect with such a rich dataset that there’ll be many more analyses and insights to come.

It’s also important to note that the study fits into a broader landscape of research into UBI and the personal and societal impacts of cash transfers — and both academic papers do a good job of providing context here.

Many previous studies on unconditional cash transfers have been inconclusive or have just hinted at tenuous associations — which is why the scale of this one if so relevant.

There are also studies on other forms of cash transfers, including lottery winnings and government support schemes. These show varying levels of impact — and they are sometimes counterintuitive (for instance, the evidence on lottery wins — contrary to popular myth — is that they increase wellbeing). But what sets UBI — and this study — apart, is that the money is transferred to participants with no strings attached.

One of the fears as I mention above is that participants in such schemes will not have the maturity or self control to use the money wisely, and that paternalistic interventions are necessary to ensure it’s used well.

However, reading through the the first findings of the OpenResearch Unconditional Cash Study, I find little if any evidence for this.

On aggregate it’s hard to tease out substantial benefits. But on a personal level there are strong indications that participants used the money in smart ways within their own context, to increase their agency in ways that suited them.

And perhaps this is one of the more important takeaways — that most people have the ability to take actions that lead to a potentially better future for them, their families, and their communities, given the chance.

But of course, this does mean actually giving them the chance. And maybe UBI is one way of helping to achieve this — especially as advanced technologies continue to transform the landscape around how people obtain and use the resources necessary to build the life and the future they aspire to.

Thank you a lot for sharing this. Now I’m studying the topic of AI and consumers with financial restrictions and these insights are incredibly valuable. Furthermore, there are many possible reflections on consumer behavior that can arise also from a more psychological point of view. Looking forward to reading the associated papers. Finally, I’m not surprised by the interest in OpenAI in this research, possibly looking for ideas and evidence regarding the AI future employment in low-income groups.

Next time you drive by Gila or Salt River Indian Reservations in Phoenix, look out the window and what you see is UBI. While there's a lot of baggage along with Native Americans one of the bigger challenges is they mostly all have UBI and they just survive.

The studies you list also reflect the same tenuous results in dozens of others from multiple different countries. It's not an outlier to have limited to no results, it's the common theme. It sounds good and I was an advocate about 10 years ago until I couldn't find any evidence that it helps at all.