How to Ensure Our Digital Legacy Isn’t Lost to the Future

We think the internet records everything, but the problem of ‘bit rot’ means all our emails and more could disappear in the decades ahead

We think the internet records everything, but the problem of ‘bit rot’ means all our emails, photos, and more could disappear in the decades ahead

How do you write down instructions that could be read and interpreted by people living 10,000 years from now? In 1992, a multidisciplinary team sat down to answer this question as they grappled with creating radioactive contamination warnings that would stand the test of time. This struggle highlights a more basic challenge that we all face when it comes to long-term information retrieval — a phenomenon that internet architect Vint Cerf termed “bit rot.”

In 1979, Congress authorized the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, or WIPP, to be built a few miles outside the New Mexico town of Carlsbad. WIPP was designed to store defense-related radioactive waste in the region’s geologically stable salt deposits. But among the many challenges the site faced was how to communicate the dangers of the buried waste to future generations.

Because of the radioactivity of the materials being disposed of, the team was tasked with creating warning “markers” that would not only endure for 10,000 years but also still be understandable by whoever was around to read them 10,000 years from now, when language and even the means of human communication could be unimaginably different.

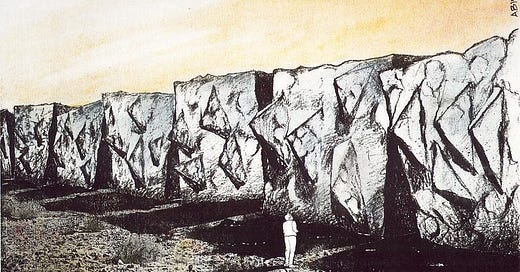

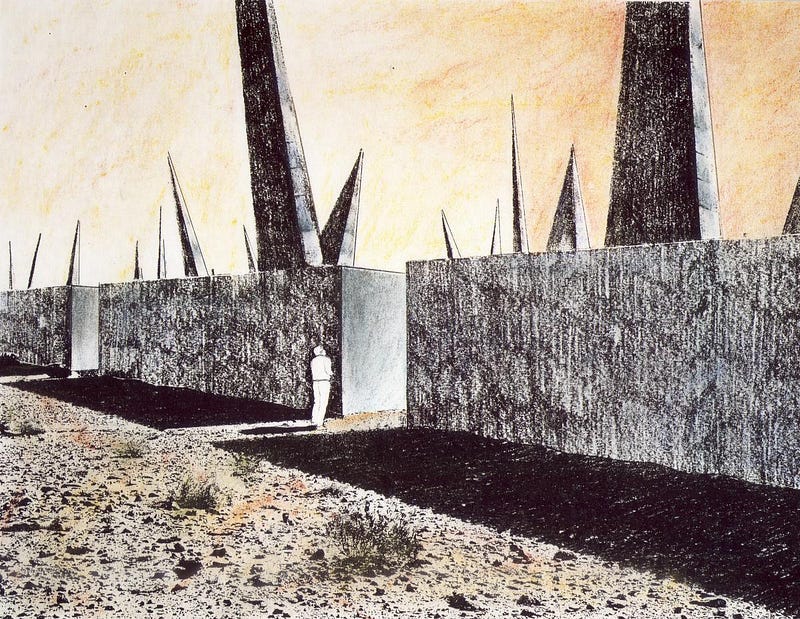

Designing these markers was the task facing the 1992 team. And it was a tough one. First, the markers needed to be durable. They needed to withstand, in the words of the team, “the tendency of human beings to vandalize structures.” They needed to provide information to future societies who might not share the designers’ language, or who exhibit very different cultural norms and expectations than we have today. And they needed to convey highly complex information about the dangers of the buried material, and how it changed over time.

In other words, a simple “Danger: Do Not Enter” sign wouldn’t hack it. Neither would print documents, digital files, or “Googleable” warnings.

Instead, the team, including the concept artist Mike Brill, developed an elegant series of marker concepts designed to transcend time, language, and culture, and to send an unmistakable message across the millennia that this was a bad place, and one to avoid at all costs. Stone, earth, and art, they concluded, are far more durable than the ephemeral information storage media we currently rely on — something that archeologists and historians are well aware of.

The WIPP markers may seem far removed from life in the 21st century, but they are a sobering reminder that in today’s data-rich world, we live under the illusion of information longevity and retrievability. With our ability to generate and store data at an exponentially accelerating rate, it’s easy to assume that what hits the internet stays on the internet. And yet, irrespective of whether this is the case — and, just for the record, it’s not — it’s our ability to read and make use of this information that really matters.

It’s as if we’ve collectively been seduced into thinking that our internet-uploaded knowledge will last forever.

This is what Vint Cerf referred to as “bit rot.” In a 2008 interview with Esquire, he claimed that, “Over a period of a hundred or a thousand years, the probability of maintaining continuity of the software to interpret the old stuff is probably close to zero. Where would you find a projector for an 8mm film these days? If the new software can’t understand, we’ve lost the information. I call this bit rot. It’s a serious problem.” It’s an idea that he pushed hard over the next few years, along with the concept of “digital vellum” as an approach to ensuring digital information can be interpreted hundreds of years from now.

These days, neither bit rot nor digital vellum gets much traction. It’s as if we’ve collectively been seduced into thinking that our internet-uploaded knowledge will last forever. And yet, there’s a danger that what we can so readily retrieve now will be indecipherable in as little as 10 to 20 years — never mind hundreds or thousands of years from now.

This has serious ramifications for the future accessibility of all the information we’re producing on a daily basis. But it also calls into question how we will be seen and understood by future generations, or even in our own lifetime. When the only way to reconstruct someone’s life is through the digital footprint that tech giants like Google and Microsoft allow us to curate, who determines how we appear to future generations, or even whether we appear at all? And in a future where deep fakes are increasingly common, how will we establish a bedrock of reality, if that reality has been “bit rotted” away?

I was reminded of how challenging it can be to recall even relatively recent aspects of our digital footprint when I recently received an unexpected package in the mail. The package contained a note from someone who worked in the same research lab as I used to many years ago. It also included an old CD-ROM.

The CD-ROM was one of my old archives, unearthed in an office cleanout. I’d burnt it in December 1999 as I was leaving my job in the U.K. to work in the U.S., and it contained my research files from the 1990s.

As a Mac user, I’d long moved on from computers with tech as archaic as a CD-ROM drive. But I managed to lash something together and was intrigued to dive into my professional life from 20-plus years ago.

The first bit of good news was that I could still access the data — CD-ROMs aren’t quite obsolete yet. That said, I have to admit that some years ago I trashed my floppy disks from the 1980s after realizing that the chances of me cobbling together some way of reading them was pretty much zero — if I’d have relied on optical disks, 3½-inch floppies, or even 5½-inch disks for my more recent digital storage, I would have been sunk.

The second bit of good news was that there were still files I could read on the CD-ROM. I still use apps like Microsoft Word and Synergy Software’s Kaleidagraph for my work, and files I’d saved in previous versions back in the 1990s were still readable. Kudos to Microsoft and Synergy Software for taking backward-compatibility seriously!

And yet, there were plenty of files that were unreadable, either because I didn’t have access to the right software, they weren’t compatible with current versions of the software, or the original software packages are simply no longer available. As a result, I have data files, mathematical models, papers, reports, and emails, that are all victims of bit rot. Unlike written records — I still have lab books from the early ’90s that anyone can read — these digital archives didn’t even last a couple of decades.

Of course, there was probably a lot of rubbish in those files. And to be sure, I haven’t felt any pangs of regret at not having them at my fingertips for the past 20 years. And yet, if someone wanted to reconstruct my work from these, or to use them to get a sense of who I was as a young researcher, they would be stumped.

This, to me, is part of the insidious danger of bit rot. We’re surrounded by so much data, and so many ways of storing and retrieving it, that we too easily lose sight of what isn’t immediately at our fingertips. The mundane and minutiae of our lives are being wiped away by what we think is important, or rather, what our app providers decide is important. This may not seem like a big deal now. But in 50 to 80 years when your children and grandchildren try to piece together your life, there will be gaping holes amidst the snippets of information that big tech has allowed to remain.

And in a century or more, who’s to say that anyone will be able to read your emails, your social media messages, your carefully crafted documents, or your digital diary?

Biographers and historians have access to a wealth of written information that helps piece together the lives of people from hundreds of years ago, or even tens of thousands of years when you consider cuneiform, cave paintings, and other forms of highly durable media.

Unless we are happy for the tech giants to control and bury our digital legacy, we need to think more carefully about bit rot.

Ironically, these earliest forms of information storage have more in common with the WIPP markers than they do with digital tech. Previous generations — because they had no other options — largely used media that was durable, that didn’t require sophisticated and temporal technologies to interpret them, and that was culturally fluid. As a result, we know more about them than generations to come may know about us.

Fortunately, the issues with potential bit rot are improving. Standardized digital formats such as PDFs and JPGs have made long-term accessibility much easier, and open standards for digital content have made it even easier to ensure file readability is independent of software developers. And yet, if you’re using a proprietary format or platform for your digital information — even if it’s well-established — you’re likely to experience bit rot one day. Maybe not next year or in a few years’ time. But the companies that own these proprietary standards won’t be around forever. And even while they are, they control your ability to access your data. Imagine a future release of Microsoft Office that doesn’t allow you to open old files (or that requires a fee for access). Or if Adobe decides that free PDF readers are not part of their future-looking business model. Or even if Google services end up disappearing behind a paywall.

None of these scenarios are likely — at least for the foreseeable future. But if we don’t want to disappear into the anonymity of bit rot, we need to get smarter we think about how retrievable our digital lives are. This might be as simple as being more intentional with how and where we save and store important information. It might mean reintroducing ourselves to time-proven technologies like pen and paper (archival quality, of course) or — like the WIPP team — turning to the longevity of meaningful artifacts. It could even be as ambitious and forward-looking as the hi.co website archive which, having been etched into a series of a 2-by-2-inch nickel plates, claimed to have a shelf life of 10,000 years.

Whatever course we take, unless we are happy for the tech giants to control and bury our digital legacy, we need to think more carefully about bit rot, and how we can preserve what’s important to us in our increasingly digitized lives. Otherwise, we run the risk of becoming digital ghosts, or worse, the merest hint of a life lived and lost, bit-rotted away to nothing.