Enter the Neo-Luddites: Transcendence, The Singularity, and Technological Resistance

On January 15, 1813, fourteen “Luddites” were hanged outside York Castle in England for crimes associated with technological activism.

From chapter nine of Films from the Future

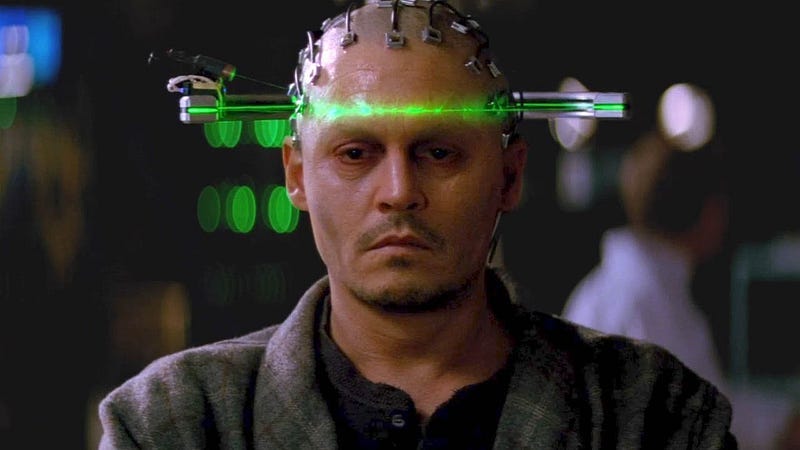

Transcendence is not a great movie — it only scored 20% on Rotten Tomatoes. But as I explore in Films from the Future, the film does provide a great starting point for exploring the emergence of convergent technologies, and the challenges of separating out plausible from fantastical speculation around the impacts of technology innovation.

This excerpt from chapter 9 of the book focuses on the Luddite movement and technological resistance — a theme that threads through the movie with the direct-action group RIFT.

On January 15, 1813, fourteen men were hanged outside York Castle in England for crimes associated with technological activism. It was the largest number of people ever hanged in a single day at the castle.

These hangings were a decisive move against an uprising protesting the impacts of increased mechanization, one that became known as the Luddite movement after its alleged leader, Ned Ludd.

It’s still unclear whether Ned Ludd was a real person, or a conveniently manufactured figurehead. Either way, the Luddite movement of early-nineteenth-century England was real, and it was bloody. England in the late 1700s and early 1800s was undergoing a scientific and technological transformation. At the tail end of the Age of Enlightenment, entrepreneurs were beginning to combine technologies in powerful new ways to transform how energy was harnessed, how new materials were made, how products were manufactured, and how goods were transported. Much like today, it was a time of dramatic technological and social change. The ability to use new knowledge and to exploit materials in new ways was increasing at breakneck speed. And those surfing the wave found themselves on an exhilarating ride into the future.

But there were casualties, not least among those who began to see their skills superseded and their livelihoods trashed in the name of progress.

In the 1800s, one of the more prominent industries in the English Midlands was using knitting frames to make garments and cloth out of wool and cotton. Using these manual machines was a sustaining business for tens of thousands of people. It didn’t make them rich, but it was a living. By some accounts, there were around 30,000 knitting frames in England at the turn of the century — 25,000 of them in the Midlands — serving the cloth and clothing needs of the country.

As the first Industrial Revolution gathered steam, though, mass production began to push out these manual-labor-intensive professions, and knitting frames were increasingly displaced by steam-powered industrial mills. Faced with poverty, and in a fight for their livelihoods, a growing number of workers turned to direct action and began smashing the machines that were replacing them. From historical records, they weren’t opposed to the technology so much as how it was being used to profit others at their expense.

The earliest records of machine smashing began in 1811, but escalated rapidly as the threat of industrialization loomed. In response, the British government passed the “Destruction of Stocking Frames, etc. Act 1812” (also known as the Frame Breaking Act), which allowed for those found guilty of breaking stocking or lace frames to face transportation to remote colonies, or even the death penalty.

Galvanized by the Act, the Luddite movement escalated, culminating in the murder of mill owner William Horsfall in 1812, and the hanging of seventeen Luddites and transportation of seven more. It marked a turning point in the conflict between Luddites and industrialization, and by 1816 the movement had largely dissipated. Yet the name Luddite lives on as an epithet thrown at people who seemingly stand in the way of technological progress, including those who dare to ask if we are marching blindly into technological risks that, with some forethought, could be avoided.

These, according to the narratives that emerge around technological innovation, are the new Luddites, or “neo-Luddites.” This is usually a term of derision and censorship that has a tendency to be attached to individuals and groups who appear to oppose technological progress. Yet the history of the Luddite movement suggests that the term carries with it a lot more nuance than is sometimes apparent.

Back in 2009, I asked a number of friends and colleagues working in civil-society organizations to contribute to a series of articles for the blog 2020 Science. I was very familiar with the sometimes critical stances that some of these colleagues took on advances in science and technology, and I wanted to get a better understanding of how they saw the emerging relationship between society and innovation.

One of my contributors was Jim Thomas, from the environmental action group ETC. I’d known Jim for some time, and was familiar with the highly critical position he sometimes took on emerging technologies, and I was intrigued to know more about what drove him and some of his group’s members.

Jim’s piece started out, quite cleverly, I thought, with, “I should admit right now that I’m a big fan of the Luddites.” He went on to describe a movement that was inspired, not by a distrust of technology, but by a desire to maintain fair working conditions.

Jim’s article provides a nuanced perspective on Luddism that is often lost as accusations of being a Luddite (or neo-Luddite) are thrown around. And it’s one that, I must confess, I have rather a soft spot for. So much so that, when Elon Musk, Bill Gates, and Stephen Hawking were nominated for the annual Luddite award, I countered with an article titled “If Elon Musk is a Luddite, count me in!”

Despite the actions and the violence that were associated with their movement (on both sides), the Luddites were not fighting against technology, but against its socially discriminatory and unjust use. These were people who had embraced a previous technology that not only gave them a living, but also provided their peers with an important commodity. They were understandably upset when, in the name of progress, wealthy industrialists started to take away their livelihood to line their own pockets.

The Luddites fought hard for their jobs and their way of life. More than this, though, the movement forced a public dialogue around the broader social risks of indiscriminate technological innovation and, in the process, got people thinking about what it meant to be socially responsible as new technologies were developed and used.

Ultimately, the movement failed. As society embraced technological change, the way was paved for major advances in manufacturing capabilities. Yet, as the Luddite movement foreshadowed, there were casualties on the way, often among communities who didn’t have the political or social agency to resist being used and abused. And, as was seen in chapter six and the movie Elysium, we’re still seeing these casualties, as new technologies drive a wedge between those who benefit from them and those who suffer as a consequence of them.

These wedges are often complex. For instance, the gig economy that’s emerging around companies like Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb is enabling people to make more money in new ways, but it’s also leading to discrimination and worker abuse in some cases, as well as elevating the stress of job insecurity. A whole raft of innovations, from advanced manufacturing to artificial intelligence, are threatening to completely redraw the job landscape. These and other advances present real and serious threats to people’s livelihoods. In many cases, they also threaten deeply held beliefs and worldviews, and force people to confront a future where they feel less comfortable and more vulnerable. As a result, there is, in some quarters, a palpable backlash against technological innovation, as people protect what’s important to them. Many of these people would probably not consider themselves Luddites. But I suspect plenty of them would be sympathetic to smashing the machines and the technologies that they feel threaten them.

This anti-technology sentiment seems to be gaining ground in some areas, and it’s easy to see why someone who’s unaware of the roots of the Luddite movement might derisively brand people who represent it as neo-Luddites. Yet this is a misplaced branding, as the true legacy of Ned Ludd’s movement is not about rejecting technology, but ensuring that new technologies are developed for the benefit of all, not just a privileged few. This is a narrative that Transcendence explores through the tension between Will’s accelerating technological control and RIFT’s social activism (RIFT is a techno-terrorist group in the movie), one that echoes aspects of the Luddite movement. But there are also differences between this tale of technological resistance and the events from two hundred years ago that inspired it, that are reminiscent of more recent concerns around direct action, and techno-terrorism in particular.

Read more at http://bit.ly/filmsfromthefuture