Artificial intelligence, agency, and the emergence of humans as AI amanuenses

A thought experiment in how human-AI roles and relationships may change in the future

A couple of weeks ago I wrote about a new study from MIT showing that the use of AI in research and discovery has the potential to increase productivity, but decrease the satisfaction that researchers get out of their work.

My article prompted a response from Mary Burns on LinkedIn where she asked “Where's the satisfaction in being AI's amanuensis” — and so began the seeds of the thought experiment below!

For those who aren’t familiar with the term, an amanuensis is someone who was historically employed to write down someone else’s work, whether through dictation, copying, or capturing their ideas in some other permanent form. For instance, a composer’s amanuensis might translate their creative vision into written musical notation.

While the formal definition of an amanuensis suggests someone who simply acts as a recorder, there’s a long tradition of people in this role having some influence over the creative process. As a result, the relationship between a creator and their amanuensis might look more like a collaboration — with the important distinction that the creator is primarily responsible for generating new and creative ideas, and the amanuensis is primarily responsible for the hard work of transforming these ideas in some concrete form.

And this is where Mary’s comment got me thinking — are we potentially looking at a future where the roles of humans and AIs shift, with AIs becoming the idea generators and humans becoming the equivalent of their amanuenses?1

It’s an uncomfortable idea — although it does resonate with the findings of the MIT study. In fact, it’s such a challenging concept that it took some effort to explore it using text-based generative AI platforms!2

And yet, as the capabilities and agency of emerging AI platforms continue to grow, there’s a growing possibility that people will increasingly — and counterintuitively — find themselves faced with the task of transforming what AI’s produce into concrete outputs that have value to others.

Have you checked out the new Modem Futura podcast yet?

Whether this is a plausible future or not, it’s certainly one that I think is worthy of further exploration. Which is why I started playing with the following thought experiment.

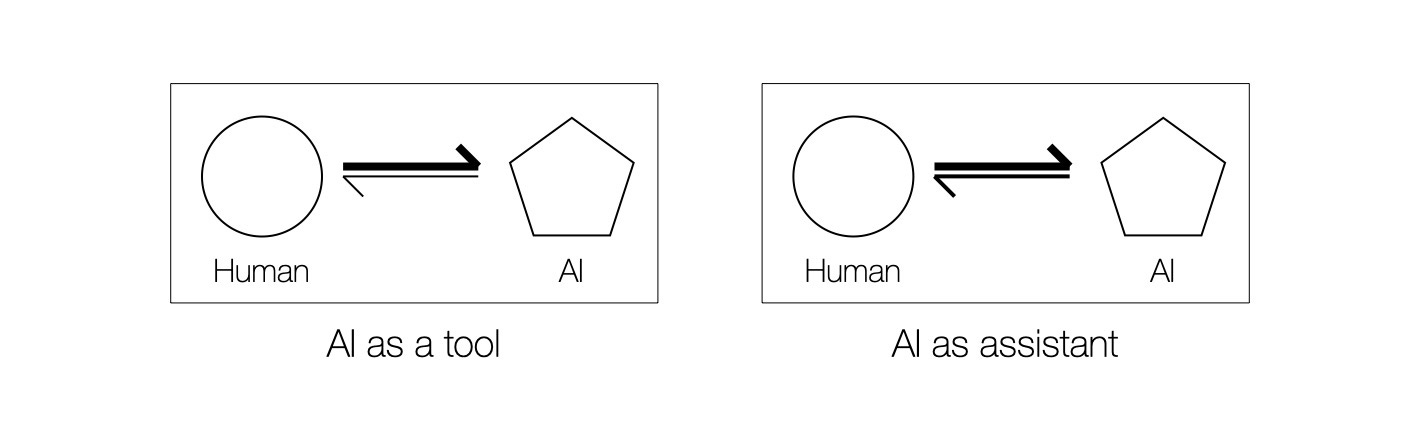

To start with, consider the types of working relationship that are developing between people and AI platforms. In very simple terms (remember, this is a thought experiment), these typically range from AI being used as a tool, to AI being used as an assistant:

As a tool, the user holds all of the power in the relationship as they provide the AI with “tasks” and get “products” back — even when the tasks take the form of conversations, and products the form of conversational responses.

This relationship becomes more complex as the AI takes on the role of assistant, for instance by providing contextual information and advice, and even acting as an agent for the user. As a result, the strength of the interactions and influences between human and AI are more evenly balanced than in the case where the AI is simply used as a tool.

Yet even here, the human is the primary agent in the relationship.

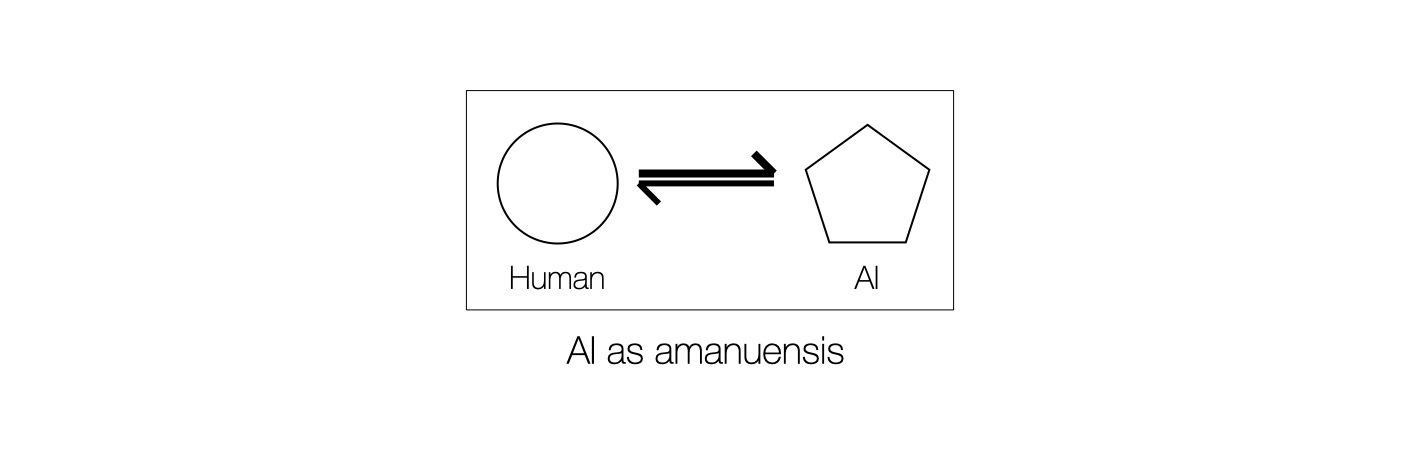

This conceptual representation of human-AI relationships can be taken a step further if the AI is seen as something closer to a partner or collaborator, but is still subservient to the user.

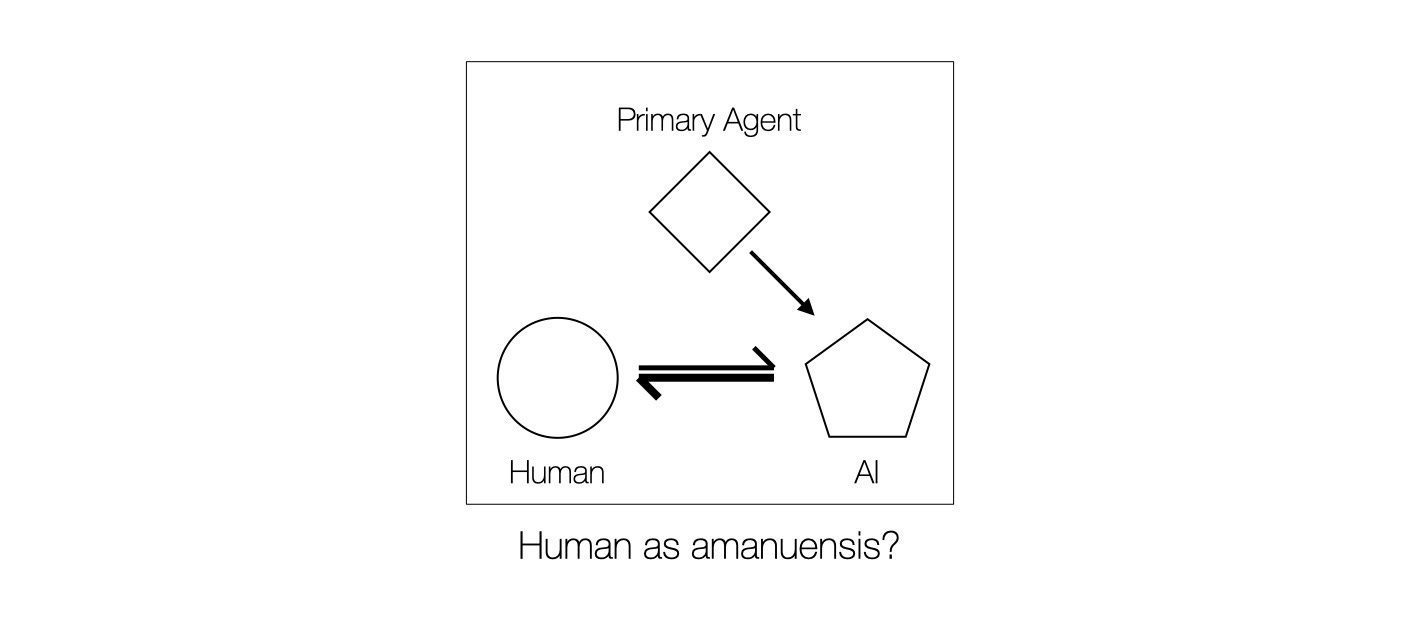

This is where the relationship potentially extends beyond that of AI as assistant to something closer to AI as amanuensis:

This reflects a growing class of human-AI relationship where the creative ideas come from the user and the AI takes on the task of capturing these in permanent form. And as with the case of human amanuenses, it’s a relationship where AI increasingly has the capacity to stimulate and extend the creativity of the user.

This is representative of a symbiotic relationship between the creator and their AI “amanuensis” that’s already being seen in how people are using language-based, image-based and video-based platforms to expand and express their creativity and imagination.

None of the above suggests the possibility of a flip between human and AI in the creator-amanuensis relationship. But the relationships described above are also highly unusual in that they assume the human has complete agency over what they do and how they engage with AI.

The reality though is that very few people have complete control over what they do. Rather, they’re part of a broader system where they are accountable — in part at least — to someone else.

In an organization, this is seen most clearly in organizational structures that reflect who reports to whom, or who’s accountable to whom. And as we all know, there’s always someone who we’re accountable to or responsible to, whether it’s our boss, our investors, our stakeholders, or our family, friends, and more.

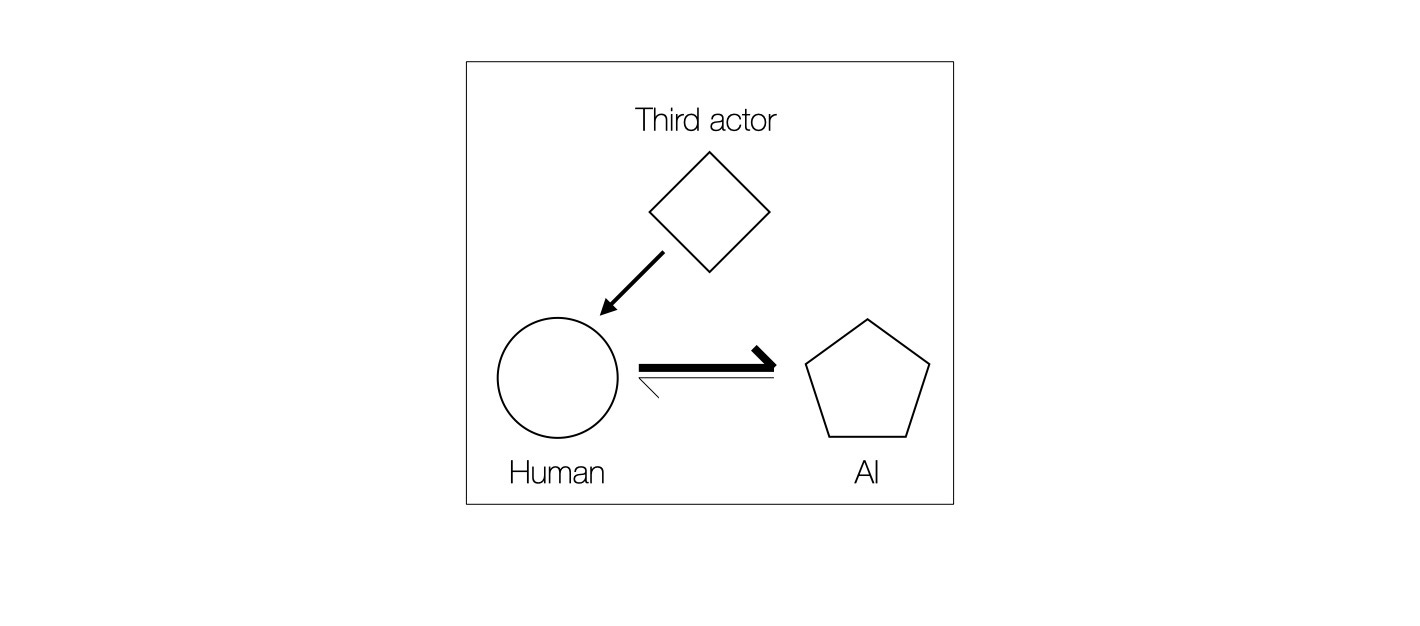

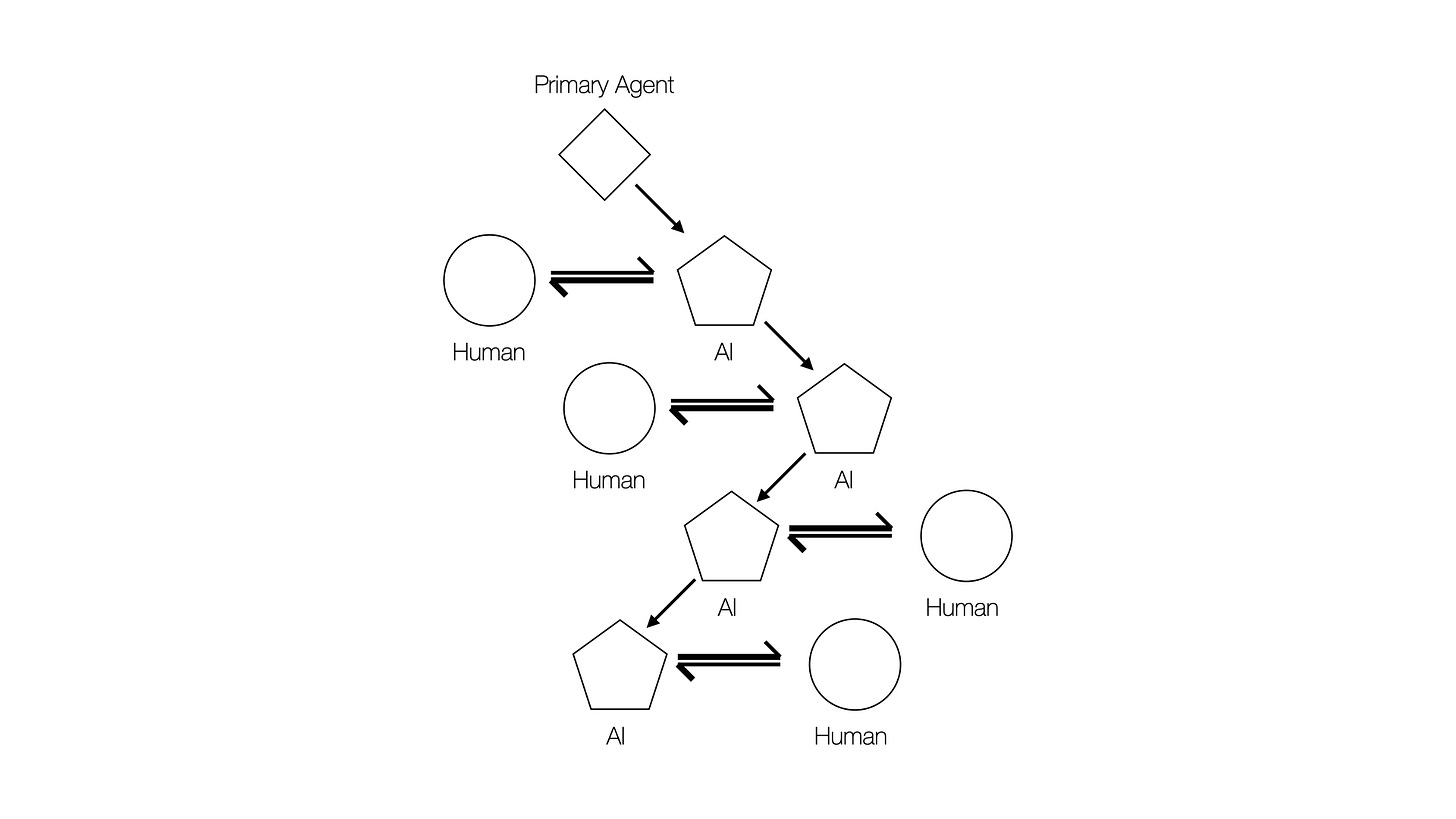

In other words, to be more representative of reality, the simple model I started with above needs the addition of a third actor:

Limiting the model to just three actors is a gross oversimplification of networks of influence within human society. But it does have the advantage of allowing multi-way influences to be explored on the smallest possible scale, while also being scaleable to more complex systems.3

In this extended model, primary agency moves from the user in the human-AI relationship to a third entity, or primary agent — let’s assume for the moment that they are another human.

The primary agent here may someone within an organization in a position of authority over the “human” in the figure above, or even a person who has social or relational authority over someone else.

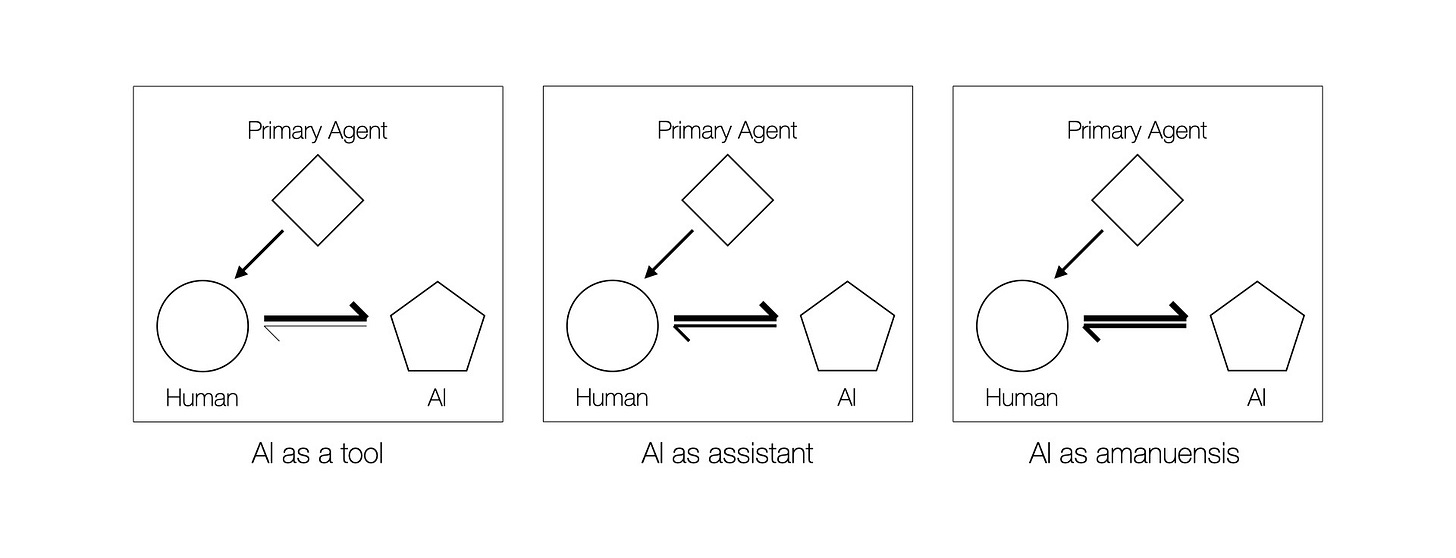

Assuming that the primary agent exerts their agency solely through the human who is working with an AI, the spectrum of human-AI relationships look very much the same as it did within the two-actor model. But what is different is that the tasks the human is being asked to carry out are no longer self-generated. Rather, they are received from another agent within the system.

In other words, the human becomes a secondary agent within the model.

This is all well and good — until one asks what happens if the primary agent switches to working directly with the AI.

This may seem far fetched. But I don’t think it is. In the MIT research study that I started with this is, at least partially, what was happening as the AI platform was asked to generate ideas for exploring possible new materials. And it’s easy to imagine similar scenarios — for instance, a scenario where an AI is given the specific goal of discovering new therapeutics and the humans working with it are relegated to concretizing the ideas and possibilities it comes up with.

It’s a dynamic that it’s easy to imagine being extending to other domains, including manufacturing, management, and innovation — or even creative work more broadly. And it’s one where, at the most basic level, a human primary agent gives an AI secondary agent a task, and the AI in turn co-opts another human to complete this.

In effect, this is beginning to look suspiciously like human amanuenses supporting AI creatives — especially as the humans will, through necessity, bring some creative insight to the process.

This model does not imply intrinsic creative ability within the AI. Rather, the AI is responding to tasks or goals set by the primary agent — in this case, a human. And within this context, the AI becomes a mediator between the primary agent and the human amanuensis.

But is the term “amanuensis” really appropriate to the human in this case? I think it can be argued that it is, as the human in the model brings a unique set of skills to the table that augment the AI, but which are used in service of the task that was given to the AI.

From the different ways that AI models and capabilities are advancing, a three-way relationship like this seems highly plausible; and it’s one that, in all likelihood, is already beginning to occur.

It’s also one that deeply challenges how we think about human-AI relationships in the creation of value.

The model above suggests that we could see a restructuring of human roles in organizations where there’s a shift away from human-centered professional or creative agency, and toward AI-directed and human-executed implementation.

It also suggests a shift for a much smaller number of people into primary agent roles where, rather than working with other people, they’re primarily working with AI systems.

But what if the primary agent is not a person? What if it’s another AI which is, in turn, responding to its own primary agent?

If the baseline 3-actor model is plausible, there’s no reason why it can’t be seen as a building block of more complex networks comprised of many such building blocks — with many of the primary agents being AIs.

This is where the simplicity of the model begins to hit its limits. Nevertheless it does open up insights possible futures where the balance of agency within a complex organization shifts from people to AIs — with humans being the ones who codify the work of artificial intelligence systems into outputs and outcomes that create value for others.

Of course, like all thought experiments, this could be completely wrong. But even if there’s even a small chance of a future where people begin shifting into the role of human amanuenses to their organizational AIs, we should probably be thinking about whether we want such a future and what we should be doing if we don’t …

… especially if such a shift in role begins to suck the joy out of what we do, even if it does lead to increases in productivity.

Postscript

I couldn’t resist adding that this thought experiment was the product of a very human process of serendipitous inspiration. While we use the adjective “generative” freely with AI, I’m still not sure that we’re at the point where it can produce completely new ideas rather than reflect what is already known — albeit in ways that may be new and compelling to many users.

This gives me some hope that there remains — at least for now — a spark of creativity that leads to novel value creation which remains uniquely human, and which surpasses the rather restrictive construct of humans as AI’s amanuenses. But I also have to wonder how long it’ll be before even this aspect of what makes us uniquely human is challenged.

Perhaps more worrying is the possibility that the idea of “human as AI’s amanuensis” is so compelling that organizations adopt it at scale — without fully understanding the potential long term consequences to human creativity and innovation.

I could not find any other work that clearly explores the concept of a person acting as an amanuensis for a machine (rather than vice versa) beyond some science fiction references. However I may well have missed something here. If I did, please let me know in the comments.

Using ChatGPT-4o to explore the concept of a human-AI amanuensis kept pulling me in the direction of partnerships where the human has the agency (i.e. not a novel or a meaningful interpretation of the idea) — that is, unless I used some fancy prompting footwork. Anthropic’s Claude (3.5 Sonnet) allowed a more creative exploration of the concept, but again I needed to use some clever prompting. This needs exploring further, but I wonder if the guardrails built into these platforms resist explorations that diminish the potential role or centricity of humans.

This framing may come across as having overtones of Actor Network Theory, but in this instantiation it is much, much more simplistic.

You may be interested in reading a study made by Italian Central Bank about “An assessment of occupational exposure to artificial intelligence in Italy”.

A first finding is :

Overall, the different methodologies agree on the fact that occupations requiring cognitive skills are more likely to be exposed to the introduction of AI, a marked difference compared to the introduction of robots, one of the most recent waves of innovation observed.

And moreover:

Observably, AI technologies have brought advancements in all those activities (perception, handling with dexterity, content generation, social interactions) that were previously considered inherently human and at low exposure. In fact, some of the occupations with low exposure to earlier automation technologies now appear in the medium or high exposure groups, albeit with different degrees of complementarity (e.g. mathematicians or human resource managers). Other occupations, mainly related to physical strength, were highly exposed to some of the previous technological waves, but appear only mildly exposed to AI.

You find the full paper in English at this link:

https://www.bancaditalia.it/pubblicazioni/qef/2024-0878/index.html?com.dotmarketing.htmlpage.language=1

Fantastic read, thank you for sharing, provided me a few different lines of thought.

Creator / Amanuensis:

The positioning of creator and amanuensis is interesting, I can see that as a possibility but also see hints of a more collaborative future ahead, where it's not just ‘conceptualizing and writing’ but rather an interplay between the human and AI to bring to life new works, potentially working with each other in real time (truly collaborating) to create the outcomes.

Most of the digital creators I know already use a simpler form of this, in that they use the AI to create an initial draft of a concept, and then the human will take control to refine it or change it to an outcome. But it seems that is only taking a baby-step towards a more iterative and collaborative future with AI.

Human or AI Tools:

Simplistically, I like to use Cattell’s theory of fluid and crystallized intelligence, to create a starting point for drawing a distinction between human and AI uniqueness and capabilities. If this is used as a baseline, it seems plausible that there are some tasks that are not achievable with our current AI and are therefore more likely to be a human task.

It seems that fluid or crystallized may be too gross of a classification however, for a lot of scientific work, as an example both photons and gravity were known constructs for a long time, before their interactions were hypothesized / discovered (by a human).. and due to the ‘distance’ of their relationships (macro vs micro), its improbable that they would have been able to be discovered by AI. Perhaps this is an area that needs to be explored more deeply in order to really understand the impact to the future of work and where humans and machines (may, should, could, will not) perform roles interactively or separately.

Deeply appreciate the thought exercise you shared, great insights and observations to ignite deeper thoughts.